Computer Chronicle 1. The First Step Toward Thinking Machines and the Foundations of Reasoning

List of Computer Chronicle Series

The plan is to publish every two weeks. However, since this is a hobby project, the schedule may be delayed or changed depending on circumstances.

| Series | Link |

|---|---|

| Computer Chronicle 0, Introduction | Link |

| Computer Chronicle 1, The First Step Toward Thinking Machines and the Foundations of Reasoning | Link |

- I have made efforts to conduct research, but if there are any inaccuracies, I welcome corrections through comments.

Discussion on the Beginning

Computers may seem intelligent, but their cleverness is an illusion. It's just a clever trick made possible by immense speed and infinite repetition. This is why nothing happening in a computer is unpredictable.

Michael A. Hiltić, translated by Lee Jae-beom, "Xerox Palo Alto Research Center", p. 131

Computers process tasks using a foolish and complicated method of rapidly turning transistors on and off. If a switch works once every second, a computer wouldn’t be necessary. Even a speed of 1,000 times a second is not practical. The switch must work about a million times a second for computers to be useful. When it reaches the speed of a billion times a second, ... computers can change the world.

T. R. Reid, translated by Kim Euidong, "The Ruler Chips of the Digital World", p. 26

To explore how computers came about, one could start from nearly any point in history. The invention of numbers, printing, writing, the concept of zero, astronomical calculations, and tools like the abacus or even animal bone fragments as calculation aids could all serve as plausible starting points.

However, covering all of these stories is impossible. Even attempting to do so would likely result in losing interest. The Timeline of Computing on Wikipedia lists many people and events. But what value would be gained from repeating that long list?

My goal is not to simply list facts. It is to explore how these facts connect, how humanity reached the concept of computers, and how they developed.

So first, let's consider what computers mean to us. Are they merely large calculators or storage devices? At one time, many people viewed computers as such.

But is that still the case for us today? I believe few people see the devices they are reading this text on as mere calculators. We issue commands to computers through keyboard input, mice, or touch interfaces, and the computer understands and performs actions as if by magic, displaying results on the screen.

Yet, hidden behind this magical appearance is a complex trick. If we look inside a computer, it is just a machine composed of a vast number of switches that distinguish on and off based on voltage levels. Thus, it can be said that, as commonly mentioned to newcomers, a computer understands only 0 and 1, or in logical terms, true and false.

Computers are magical objects, yet they are also incredibly simple collections of switches. But there is a vast gap between these two explanations. How can a machine made of switches that can express only two values understand our commands and perform all these processes, even displaying results?

I will not delve into the origins of numbers or tangential stories like clockwork devices. Instead, I intend to talk about the process that fills in this gap.

This journey began with brilliant ideas leading to the concept of today's computer, how that concept was built, and what was created to make it relatable to people. We seek to understand how switches transformed into what seems like magic to us.

This narrative can be divided into two main streams.

One is the history of concepts. Computers emerged from a multitude of concepts built by many individuals. People in the early 20th century formalized reasoning, dreaming of a complete system that could compute everything, only to feel frustrated. From that frustration, computers were born. There were many advancements thereafter that allowed computers to appear as they do today, including Turing machines, circuit theory, and the von Neumann architecture, as well as user interfaces that belong to this stream.

The other is the history of machines. The reason computers did not just remain ideas in minds but were placed on our desks was the concurrent development of physical devices. This includes switches, vacuum tubes, and transistors, adding machines that rotated levers and automatic calculators that read punch cards, up to integrated circuits and screens. These elements make up what we now refer to as hardware.

These two streams evolved separately, occasionally converging, and eventually flowed together seamlessly over time. Thus, computers emerged as an amalgamation of ideas, metals, switches, symbols, circuits, and languages across time.

So where do we start?

If I had to choose a starting point, it would be reasoning. Humans have long contemplated how to derive new truths from known facts. The desire to formalize thought processes and further convert them into calculations gave birth to computers. So let us take the first step into reasoning.

The First Reasoner - Aristotle

Reasoning is a discourse in which, from a few established things, something else necessarily follows from those established things.

Aristotle, "Topics", Book 1, Chapter 1, 100a25-271

Syllogism

The invention of a format to derive new judgments from established facts marked a significant turning point in the history of philosophy. At the starting line is Aristotle, a philosopher from ancient Greece who is well-known even to those uninterested in philosophy.

Aristotle studied a form of reasoning known today as syllogism. It is unclear if he directly articulated this statement, but a classic example is as follows:

Premise 1: All humans are mortal.

Premise 2: Socrates is human.

Conclusion: Therefore, Socrates is mortal.

He derived a new proposition (conclusion) from two structured premises. At first glance, this seems simple and obvious. Socrates is human, and all humans are mortal, so isn't it natural that Socrates is mortal?

However, this style of reasoning was not about questioning which propositions were correct. The essence was creating a method to identify something new that necessarily follows from existing facts through the laws of thought.

Aristotle believed that such reasoning could take on a certain form. He organized rules to derive conclusions using sentences that took one of the following four forms2.

| Sentence Form | Example |

|---|---|

| All are | All humans are mortal. |

| is not | Trees are not animals. |

| Some are | Some dogs are obedient. |

| Some are not | Some dogs are not obedient. |

This was the beginning of the idea of "rules for generating new facts through logic." Subsequent attempts to expand this logical system and refine it without contradictions formed the theoretical basis of computers.

Following developments, such as those by Leibniz, also started with Aristotle's logic. However, before diving into that narrative, let's briefly look at previous attempts to refine this logic and draw out new facts.

Later Attempts at Development

Philosophers of the Stoic school, including Chrysippus, introduced new connectives like "if ... then ..." into this logic. They expanded the logical structure to engage in discussions similar to what is known today as propositional logic.

Medieval Scholastic philosophers explored the logical functions of expressions like "in as much as" and "except." They primarily employed this logic for philosophical arguments about God.

Among such philosophers, an interesting figure was Ramon Llull, a 13th-century philosopher and poet. He proposed methods for generating new questions and facts by combining 18 fundamental concepts like goodness, greatness, and eternity. He even created a tool called the Lullian Circle to assist in this reasoning.

Llull's goal was not the development of formal logic in a modern sense. He sought to create a perfect logic about God that everyone could agree on through such reasoning. His aim was to persuade Muslims to convert to Christianity through this logic. Regardless of his intent, it is clear that he was an early individual attempting to mechanically perform logical reasoning.3

The Dream of Perfect Reasoning - Leibniz

The only way to correct our reasoning is to write it as clearly as mathematical symbols so that we can instantly notice any errors. If we can do that, when conflicts arise, we can say, "Let’s calculate!" Then we'll know who is right.

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, quoted in P. P. Wiener, "Leibniz Selections" (1951)

Leibniz's Dream

In 1646, 2,000 years after Aristotle formalized logic, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz was born. He would later be referred to as one of the greatest mathematicians in history, but it was ordinary teachers in Leipzig who first taught him mathematics.

These teachers introduced Leibniz to Aristotle's logic from two millennia prior. Here, Leibniz conceived what he called "wonderful ideas." His thoughts were inspired by Aristotle's division of concepts into categories.

Leibniz imagined a system of symbols that could describe the entire world, much like how all words in English can be represented by the 26 letters of the alphabet, assigning meanings to each symbol he proposed. In this imagined system, calculations using laws would enable the determination of truth or falsehood regarding statements and the discovery of logical relationships.

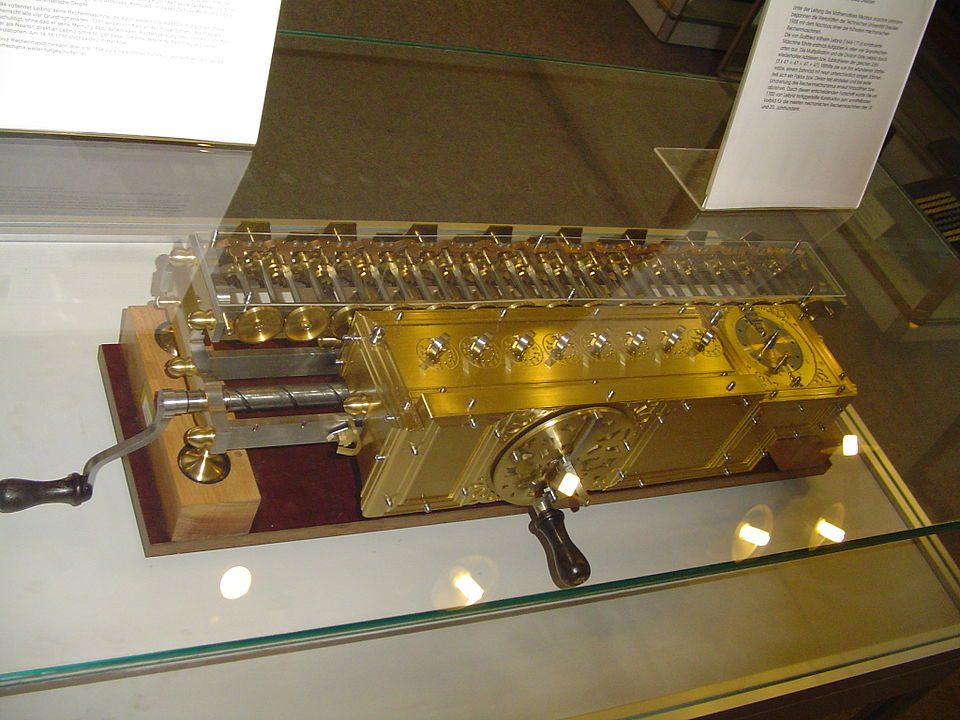

From that point on, Leibniz lived his life pursuing this dream: replacing logical reasoning with symbolic calculations and constructing a machine to perform these calculations. As part of this vision, in 1673, he created a mechanical calculator capable of performing arithmetic using gears, shown in the following picture (modern-day reproduction).

The mechanical device used here would later be known as the "Leibniz Wheel" and was used into the 1900s. While earlier machines existed for addition and subtraction, Leibniz was the first to create a calculator that could also perform multiplication and division.

Though only a machine capable of arithmetic was actually implemented, Leibniz looked further down the road. The year after creating the calculator, he envisioned a machine for solving simultaneous equations. The following year, he wrote that his goal was to replace logical reasoning with calculations and build a machine to perform these calculations.

Leibniz’s plan was to create a knowledge compendium encompassing all human knowledge. Next, he aimed to extract a few fundamental concepts that formed the basis for this knowledge and assign appropriate symbols to them. He believed that manipulating these symbols according to the laws of reasoning would allow knowledge to be inferred. In modern terms, this is referred to as "symbolic logic." Leibniz believed that through this symbolic logic, it would be possible to explain everything in the world.4

We often praise those who develop interesting problems that are not practical in real life, such as counting the number of regular polyhedra. (...) But how much more valuable is it to derive our greatest ability—human thought—into mathematical laws?

Leibniz5

He also established rules for handling this symbolic logic. These included several principles later independently discovered within Boolean algebra. Leibniz proposed using the symbol to express combinations of logical terms, suggesting rules like and .

Leibniz's Beliefs and Future Directions

Leibniz believed that God had a clear intention to perfectly determine everything in the world. He viewed the arrangement of the world as something that could be inferred through meticulous manipulation of symbols. One of the lasting legacies of this thinking is the integral symbol we use today.

We accept the symbol as an integral meaning in itself, and if we know how to integrate, we can naturally calculate any expressions containing that symbol. Leibniz perceived that everything in the world could be explained through calculations of symbols with universal meanings. He also believed that one day, machines would be able to perform these calculations.

Just as Ramon Llull sought to create arguments for God using basic concepts in the 13th century, Leibniz aimed to express everything in the world through symbols and reason through the aforementioned rules.

During his lifetime, Leibniz's logical thinking went mostly unnoticed and was not rediscovered until the late 19th century. Therefore, he did not have a significant impact on the logicians of his time or shortly thereafter.

However, logic ultimately flowed in the direction Leibniz envisioned. People endeavored to express more propositions about the world in logic and symbols and establish rules for manipulating them. Later thinkers believed they could automatically generate new propositions by extracting and organizing more foundational rules from this.

This process led to the emergence of George Boole. To properly handle propositions, they had to be expressible in a mathematical form. The first person in history to establish a proper system for expressing and handling propositions was George Boole. He can be seen as the first to realize to some extent the potential Leibniz dreamed of.

Boole Establishes Symbolic Logic

Those familiar with abstract algebra theories know that the validity of an analysis depends not on the interpretation of the symbols used but solely on the laws by which those symbols combine.

George Boole, "The Mathematical Analysis of Logic," Introduction

Representing Groups with Symbols

In 1815, during a time when Leibniz's dream was still shrouded in silence somewhere in a drawer, George Boole was born in Lincoln, England, the son of a shoemaker.

By the age of 16, Boole was already teaching while studying mathematics. He had very little money for books, and since math books took a long time to solve after purchasing, they were considered a worthwhile investment for him. One day, while walking in the fields, he reportedly had the inspiration that it might be possible to express logical relationships using algebraic laws.

Later, while running a school in his hometown and interacting with fellow mathematicians, he further developed this inspiration. He realized that words indicating types, such as "dogs" or "black things," were significant in logic, as in the sentence, "Some dogs are black."

Boole then conceived the idea that these properties or groups could be expressed using English symbols. By doing so, he believed he could handle logical elements just like mathematical calculations. As will be explained in the next section, he was correct.

His idea was to use to represent "dogs" and for "black things." Boole also created a method to express operations similar to today's intersection. If both and are symbols representing groups, then denotes something that belongs to both, so in this case, represents "black dogs."

What about ? As mentioned, if denotes "dogs," then means "dog and dog," which is simply "dog." This rule becomes the foundation of Boole's entire logical system. He also created operations known today as union and difference, represented by and , respectively.

Boole also came up with an idea similar to how computers represent everything in binary. The algebra of logic consists of a mathematical system composed only of 0s and 1s. This was somewhat an intuitive flow. Earlier, Boole viewed as one of the fundamental rules of his logical system, and considering when holds true in general mathematics reveals that it is only cases where is 0 or 1.

Boole's Established Symbolic System

Boole's greatest achievement was advancing a step from Aristotle's system, which only handled limited forms of reasoning. He used symbols to represent groups, establishing rules for manipulating them, thereby enabling mathematical handling of logical relationships.

Aristotle's syllogistic reasoning dealt with conclusions derived from premises required to conform to one of the four fixed formats. However, Boole pointed out that many problems could not be expressed using these four formats and that there were many relationships of premises that could not be represented by syllogistic logic. He used the English symbols he had proposed to represent these relationships. He also offered new ways to derive conclusions from these logical premises.

For example, consider these premises6:

- Either mom or sister ate the cake.

- Mom did not eat the cake.

These are very simple premises, and anyone with a basic understanding of logic could easily conclude that "the sister ate the cake." However, these premises cannot be expressed in Aristotle’s syllogistic form. In Boole’s logical system, it is possible! We can represent the components of these premises in symbols:

- : Mom is the one who ate the cake.

- : The one who ate the cake is the sister.

If we express falsehood as and truth as , and use Boole's logical sum and product symbols, we can represent these premises as follows:

Thus, we can naturally derive the conclusion . Therefore, the one who ate the cake is the sister. Boole provided a method for expressing logical relationships as symbols and deducing from them. This allowed for a broader scope within the logical system. This had a significant impact on the subsequent representation of logical operations as symbols within computers.

However, there were still incomplete aspects in Boole's established system. To reach the idea of computers, it was necessary to recognize the efforts required to fill these gaps and that such systems inherently possessed limits that could not be overcome.

Yet, the new framework Boole introduced laid the groundwork for the logical systems that would come later. In the next piece, we will learn about the people who worked to fill these gaps in such systems.

References

General computer science knowledge covered in typical courses significantly helped in understanding this research.

Books

Martin Davis, translated by Park Sang-min, "Today We Call Them Computers," Insight

Aristotle, translated and annotated by Kim Jae-hong, "Aristotle's Analytic Prior," Seogwangsa

Anthony Kenny, translated by Kim Young-geon et al., "History of Western Philosophy," E.G. Books

Kawazoe Ai, translated by Lee Young-hee, "How Are Computers Made?" Road Book

Apostolos Doxiadis, Christos H. Papadimitriou, illustrated by Alekos Papadatos, translated by Jeon Dae-ho, "Logicomix," R.H. Korea

Websites

Wikipedia, Ramon Llull

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ramon_Llull

Wikipedia, History of Logic - especially the section on Stoic Logic and Medieval Western Logic

https://ko.wikipedia.org/wiki/%EB%85%BC%EB%A6%AC%EC%82%AC

Hello, Stoic Owl!

https://brunch.co.kr/@nomadia/49

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Aristotle’s Logic, section 5. The Syllogistic

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/aristotle-logic

Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, George Boole

https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/boole/

Jonathan Gray, "Let Us Calculate!" Leibniz, Llull, and the Computational Imagination

Footnotes

-

Aristotle, translated and annotated by Kim Jae-hong, "Aristotle's Analytic Prior," Seogwangsa, 2024, p. 34 ↩

-

For more about these rules, see Martin Davis, translated by Park Sang-min, "Today We Call Them Computers," pp. 43-45. A more detailed explanation of Aristotle's proposed rules can be found in the preface to "Analytic Prior." ↩

-

Ramon Lull Invents Basic Logical Machines for the Production of Knowledge ↩

-

Martin Davis, translated by Park Sang-min, "Today We Call Them Computers," Insight, pp. 19-20 ↩

-

G.H.R. Parkinson, "Leibniz-Logical Papers," Oxford University Press, New York, 1966, p. 105 ↩

-

This example is almost directly taken from the pages 128-137 of Kawazoe Ai, translated by Lee Young-hee, "How Are Computers Made?" ↩