Diving into the JavaScript Event Loop

While searching for the reasons why setTimeout is inaccurate, the topic of the event loop emerged, which became too lengthy, resulting in this article being divided.

1. Web Standards

There are no asynchronous methods such as setTimeout or setInterval found in the JS specification when scrutinized closely. The same goes for console.log and others. However, nearly all JS host environments available in the market provide such methods.

These are not included in the W3C specified JavaScript standard (ECMAScript) but are part of the WebAPI standard specified by WHATWG. One can think of it as a bundle of APIs created to operate in browsers. Most JS host environments, in addition to browsers, support this.

Besides setTimeout, other items like console, fetch, and XMLHttpRequest are also included in the WebAPI.

2. WebAPI and JS Engine

We generally do not pay attention to which standard each function belongs to while using them. No matter what standard setTimeout is included in, can we not use it when writing JS?

However, internally this must be managed properly. How do WebAPI and the JS engine interact?

2.1. JS Engine Area

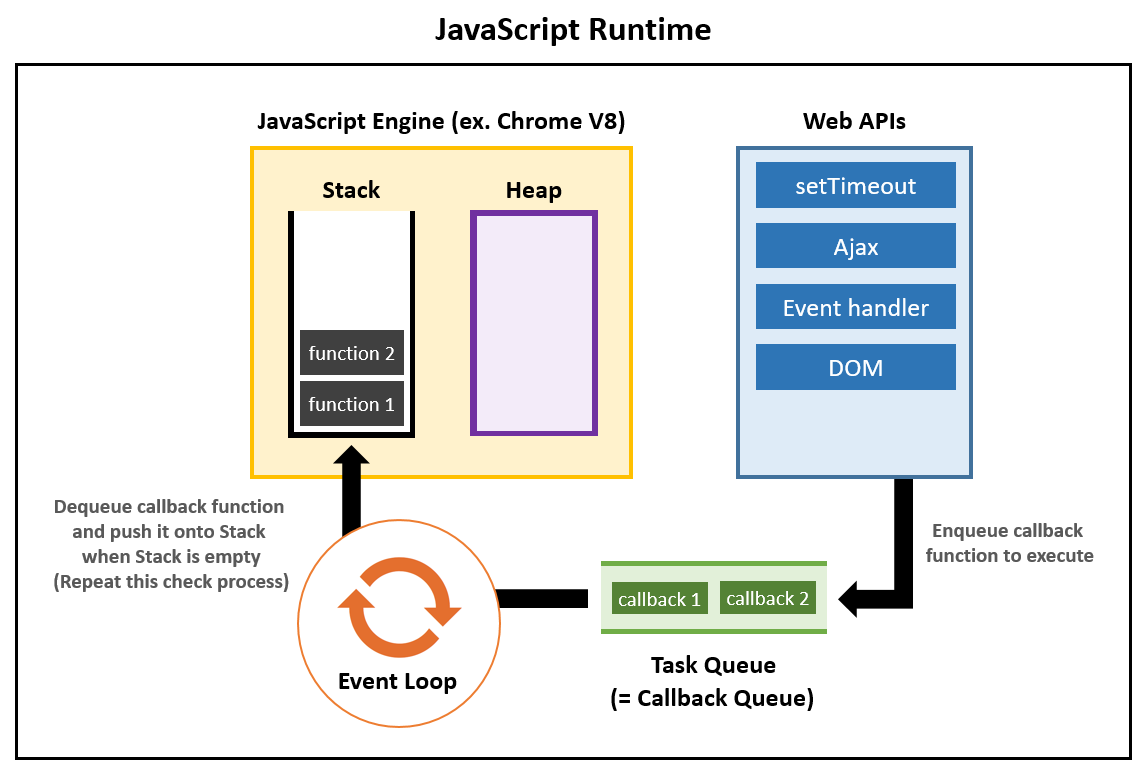

The call stack is the area managed by the JS engine. In JS code execution, functions are stacked in the order they are called, and as in a stack data structure, they are executed one by one from the top. Once a function execution is complete, it is removed from the stack.

Since JS is single-threaded, it can only do one task at a time. Therefore, there is only one call stack that manages all called functions. The size of this call stack is limited; if it exceeds its limit, a 'Maximum call stack size exceeded' error occurs.

The heap, on the other hand, is where variables and objects are stored, providing the necessary data when functions in the call stack are executed.

2.2. About WebAPI

As mentioned above, since JS is single-threaded, it can only handle one task at a time. However, we can perform tasks simultaneously in the browser. This is thanks to the APIs provided by the browser or JS host environments, called WebAPI.

WebAPI manages asynchronously executed APIs, such as setTimeout, fetch, and XMLHttpRequest. These APIs are managed by the JS platform itself so that they do not block the progress of the JS call stack. This means that the APIs managed by WebAPI can run concurrently, separate from the JS interpreter, which can only perform one task at a time.

Furthermore, WebAPI is not written in JS but in other languages like C, which allows it to perform tasks that are not possible in standard JS, such as sending AJAX requests or manipulating the DOM.

2.3. Task Queue (Callback Queue)

Through WebAPI, we can perform tasks concurrently, separate from the JS interpreter (which can only handle one task at a time). However, how do WebAPI and JS code interact? For example, if we receive information from a server via an AJAX request, how does JS process it? The answer lies in the task queue.

All WebAPI functions operate asynchronously, meaning they have callback functions. WebAPI allows the code for these callbacks to execute after the API call is complete.

When we execute the following code, it outputs a, c, b in order.

console.log("a");

setTimeout(() => {

console.log("b");

}, 0);

console.log("c");

This is due to how setTimeout operates. It executes while the JS interpreter runs the next commands. After the specified delay, the callback function will execute.

However, this callback function is naturally written in JS. Therefore, the JS interpreter must execute this callback function, which means the callback must enter the call stack.

Nonetheless, there may already be other functions executing in the call stack. Thus, the callback function will be placed into a queue known as the task queue.

The processing of setTimeout proceeds as follows:

setTimeoutis executed.- This

setTimeoutis passed to WebAPI. - WebAPI passes the callback function of

setTimeoutto the task queue after the specified delay has passed. - When the event loop runs and the call stack is empty, it takes the top callback from the task queue and places it into the call stack.

For example, consider the following code.

setTimeout(foo, 1000);

This means setTimeout will pass the instruction to execute the callback function foo after one second to WebAPI.

WebAPI will utilize this information to send the callback function to the task queue after one second. For other asynchronous methods, it will send the callback function to the task queue at the appropriate time based on the corresponding information. The event loop then sends the top callback from the task queue to the call stack when it is empty.

2.4. Need for Optimization

If the call stack is currently executing some code, the event loop will be blocked. This means that if there are ongoing tasks in the call stack, the tasks in the task queue cannot be passed to the call stack until they complete and the call stack is completely empty. Additionally, considering the structure of the queue, callback functions must be executed in the order they stacked in the queue.

This necessitates optimization. If too much code is executed in the call stack or too many tasks are assigned to the task queue, it may prevent new tasks from being executed while processing tasks in the task queue.

For instance, when scrolling, an enormous amount of events gets added to the task queue. If processing scrolling events takes some time, it will be difficult to quickly handle the numerous user click events that accumulate subsequently in the task queue, due to processing the scroll events sequentially.

Therefore, techniques such as debouncing—which prevents function calls from occurring in intervals shorter than a specified time—and throttling, which only executes either the last or first among sequential function calls, must be employed.

2.5. Asynchronous Methods

To execute a task asynchronously, one can simply create a callback function and pass it to setTimeout, using it like setTimeout(func, 0).

Then, the task corresponding to func will execute as quickly as possible during the next event cycle. However, there are also tasks that must be executed strictly after asynchronous tasks, such as processing data after retrieving it from a database.

In such cases, nested setTimeout calls can be used.

function A() {

console.log("A");

}

function B() {

console.log("B");

}

function C() {

console.log("C");

}

setTimeout(() => {

A();

setTimeout(() => {

B();

setTimeout(() => {

C();

});

});

});

Of course, writing code in this manner can lead to the well-known "callback hell," for which various solutions such as Promises and async/await exist. However, that is not the focus of this discussion; we will explore the operation of Promises in the future, though the patterns of their use go beyond this article.

3. Operation of Promises

However, we know another method to achieve asynchronous behavior in JS. This method also enforces order—namely, Promises. How do Promises operate?

3.1. What are Promises?

We saw earlier that asynchronous code can be written using setTimeout. The same can be done using Promises.

new Promise((res, rej) => {

res();

})

.then(() => {

A();

})

.then(() => {

B();

})

.then(() => {

C();

});

Of course, one can also use async/await or write the same Promise differently. However, the important thing is to understand how Promises work. How does the above code operate asynchronously?

3.2. Job Queue

Promises operate differently from the callback method. Promises have their own separate queue, referred to as the job queue or promise queue.

This queue takes priority over the task queue, meaning that the event loop processes the promise queue before the task queue.

Let’s look at the following code.

function A() {

console.log("A");

}

function B() {

console.log("B");

}

function C() {

console.log("C");

}

A();

setTimeout(B, 0);

new Promise((resolve, reject) => {

resolve();

}).then(() => {

C();

});

console.log("D");

The above code outputs A, D, C, B in order. The outputs of B and C are processed asynchronously, so it is natural that A and D are printed first. Additionally, because the event loop prioritizes the promise queue, C is output first, followed by the processing of the task queue, which outputs B.

There are further details about this subject available at the following links, but I will postpone them until I have acquired more knowledge.

https://ko.javascript.info/microtask-queue

https://ko.javascript.info/event-loop

References

https://ssocoit.tistory.com/249

https://ko.javascript.info/settimeout-setinterval

https://negabaro.github.io/archive/js-async-detail

https://felixgerschau.com/javascript-event-loop-call-stack/#web-apis