Exploring JavaScript - Where is Symbol Used?

Introduction

When learning JS for the first time, one typically explores the basic value types, known as primitive values. This often involves encountering a description similar to the following:

In JavaScript, a primitive value (or primitive data type) is data that is not an object and has no methods. There are 7 types of primitive values: string, number, bigint, boolean, undefined, symbol, and null.

Among these 7 kinds of primitive values, most are utilized frequently during development and have clear purposes. For instance, developers using JS would have no doubt about the utility of string values. Although bigint may not be frequently seen, its name alone conveys its purpose and usage.

However, one value stands out as relatively unfamiliar: the symbol. Given how important and prevalent other primitive values are in JS, one might even question why the symbol occupies a position among them.

Therefore, I investigated what a symbol is and where it is used. Although symbols may not be commonly used at the application level, they play a crucial role in the internal implementation of JS by creating unique values.

1. Introduction to Symbol

Let's first define what a symbol is and how it can be used.

1.1. What is Symbol?

A symbol is one of the primitive data types introduced in ES2015. Symbols can be created using the Symbol() constructor function, which guarantees their uniqueness across the entire program. To avoid confusion, the new operator is not supported when using the Symbol constructor.

// Creating a symbol

let id1 = Symbol();

let id2 = Symbol();

// Each symbol is unique, so this expression evaluates to false

console.log(id1 == id2);

// A TypeError occurs if new is used

let newSymbol = new Symbol();

1.2. Description Argument of Symbol

As mentioned earlier, symbols can be created using the Symbol() constructor function.

When creating a symbol, a string can be passed as an argument to the Symbol() constructor to attach a description, which can be useful during debugging.

let id1 = Symbol("id");

console.log(id1);

This description will also be displayed when converting the symbol to a string using the toString() method. Notably, a symbol cannot be automatically coerced into a string. For example, passing a symbol as an argument to alert will produce the following error:

Uncaught TypeError: Cannot convert a Symbol value to a string

Hence, using the previously mentioned toString() method allows the symbol to be displayed in string form.

let id1 = Symbol("id");

alert(id1.toString()); // Symbol(id)

In fact, the description passed to Symbol() has no practical use beyond debugging. While the description property can retrieve the description used during symbol creation, comparing symbols using this description is unnecessary since symbols are inherently unique.

let id1 = Symbol("id");

alert(id1.toString()); // Symbol(id)

alert(id1.description); // id

Creating identical symbols with the same description does not affect their uniqueness; thus, the argument provided to the constructor serves as merely an identifier.

1.3. Global Symbol Registry

As mentioned earlier, symbols are guaranteed to be unique regardless of the string passed as an argument to the Symbol() constructor.

However, symbols created in separate scripts cannot be shared easily, making it challenging to access them outside of their originating context. For example, how do you access a symbol key created within an object?

// How to access a key in an object like this?

{

[Symbol()]: {

msg: "Hello"

}

}

By using the global symbol registry, symbols with the same name can point to the same object.

1.3.1 Symbol.for(key)

Symbol.for(key) searches for a symbol with the given key in the runtime symbol registry and returns it if it exists. If not, it creates a new symbol in the global symbol registry using that key and returns it.

Thus, calling this function with the same key will always return the same symbol within the same runtime environment.

// A symbol with id is registered in the global symbol registry

let id = Symbol.for("id");

// Returns already registered symbol

let id2 = Symbol.for("id");

// true

alert(id === id2);

1.3.2 Symbol.keyFor(sym)

Symbols created using Symbol.for(key) can be queried for their key using Symbol.keyFor(sym).

let id = Symbol.for("id");

let witch = Symbol.for("witch");

// id

console.log(Symbol.keyFor(id));

// witch

console.log(Symbol.keyFor(witch));

This function searches the global symbol registry to retrieve the name of the symbol passed as an argument. If the symbol is not registered in the global symbol registry, it returns undefined. As will be explored later, well-known symbols are not registered in the global symbol registry.

console.log(Symbol.keyFor(Symbol.iterator)); // undefined

If you want to obtain the string argument passed when creating a non-global symbol, you should use the description property mentioned earlier.

let id = Symbol("test");

console.log(id.description); // test

2. Purpose of the Symbol Type

So, why was the symbol created? The original purpose was to create private properties. Given JS's nature of using objects as prototypes rather than classes, the aim was likely to create properties that could be accessed solely from within the object itself.

Immediately Invoked Function Expressions (IIFE) can also create private properties using closures, suggesting a desire to apply this concept to object properties as well.

However, with methods such as Reflect.ownKeys emerging, which allow access to symbol keys within an object, symbols have drifted from their original purpose.

Nevertheless, the unique characteristics of symbols—signifying that duplicate keys cannot occur—remain useful, as they allow for properties to be created without the worry of name collisions.

This is somewhat analogous to Python's __ convention for private property names. However, properties declared with Python's convention can be accessed through _ClassName__VariableName. In this regard, symbols provide a more elegant solution by creating complete unique values rather than simply relying on naming conventions.

Next, let's explore where these symbols can be applied, focusing on the limited application-level use cases.

3. Usage for Defining Constants

There are instances where values themselves hold no meaning, and it is the constant names that do. When trying to implement a usage similar to enums in JS, a frozen object using Object.freeze is employed.

For example, we can define constants as follows:

const Direction = Object.freeze({

UP: 'up',

DOWN: 'down',

LEFT: 'left',

RIGHT: 'right',

});

In this case, Direction.UP is, in fact, equivalent to the string 'up', thus increasing the possibility of value collisions. For instance, Direction.DOWN === COMMAND.DOWN could occur.

This could lead to a situation where a direction is indicated, but instead, an important command might be issued. To prevent value duplication in such cases, using symbols could allow for more robust code design.

With this, each constant holds a unique value, while the string provided during symbol creation can be used for debugging.

const Direction = Object.freeze({

UP: Symbol('up'),

DOWN: Symbol('down'),

LEFT: Symbol('left'),

RIGHT: Symbol('right'),

});

While not a common practice, this approach has also been utilized in the React project code.

export const meta = {

inspectable: Symbol('inspectable'),

inspected: Symbol('inspected'),

name: Symbol('name'),

preview_long: Symbol('preview_long'),

preview_short: Symbol('preview_short'),

readonly: Symbol('readonly'),

size: Symbol('size'),

type: Symbol('type'),

unserializable: Symbol('unserializable'),

};

4. Creating Hidden Properties Using Symbols

Symbols can be employed as property keys within objects. Symbol keys are ignored by typical property retrieval methods such as for..in, Object.getOwnProperties(), or Object.keys().

const mySymbol = Symbol('mySymbol');

const obj = {

nickname: 'witch',

age: 18,

[mySymbol]: 'hello'

};

/* nickname: witch

age: 18 */

for (let key in obj) {

console.log(key, obj[key]);

}

console.log(Object.keys(obj)); // [ 'nickname', 'age' ]

Using this characteristic of symbols allows for the creation of properties that generally cannot be retrieved, effectively enabling hidden properties in objects.

4.1. Creating Hidden Attributes in Objects

Such hidden properties can primarily serve to record metadata within an object, creating properties that external code cannot easily access or overwrite.

const userInternalKey = Symbol('userInternalKey');

let user = {

nickname: 'witch',

[userInternalKey]: 32951235,

};

This can also be utilized within classes or constructor functions, adding hidden properties to all instances of that constructor or class.

const mySymbol = Symbol('mySymbol');

class MyClass {

constructor() {

this[mySymbol] = 'foo';

this.prop = 'bar';

}

getMyValue() {

return this[mySymbol];

}

}

const myClass = new MyClass();

console.log(myClass.getMyValue()); // foo

console.log(Object.getOwnPropertyNames(myClass)); // [ 'prop' ]

4.2. Adding Properties to External Objects

Is there a practical way to leverage this? What scenarios might require the creation of properties that are easily untraceable in an object while ensuring no name collisions?

There could be various scenarios, but a common one involves needing to add unique properties to objects sourced from external library code.

Consider an user object obtained from an external library:

const user = {

name: "witch",

nickname: "witch",

position: "developer",

age: 25

}

Suppose you want to add an isWorking property to this object. You could simply add it directly as follows:

user.isWorking = true;

However, doing this can lead to several issues.

The most prevalent problem arises when the external library uses object property lookup functions like for..in or Object.keys(). Your added property may cause unexpected results. This aspect will be discussed in further sections.

Additionally, if the library authors later decide to add an isWorking property to the user object, your attribute could conflict with theirs. It’s even possible that a standard committee may decide to add this property to all objects.

These issues can be resolved by using symbols as keys for external objects. As previously mentioned, symbols are guaranteed to be unique throughout the program, and are ignored by property retrieval codes such as for..in. Furthermore, Symbol("isWorking") is distinct from "isWorking", so there are no concerns about collisions.

const user = {

name: "witch",

nickname: "witch",

position: "developer",

age: 25

}

const isWorking = Symbol("isWorking");

user[isWorking] = true;

This mechanism leverages the fact that external scripts cannot easily access properties with symbol keys. (This does not imply that they are private; internal logic like sym in obj can access symbol keys, and methods like Object.getOwnPropertySymbols() or Reflect.ownKeys() can also retrieve them. Additionally, Object.assign does not ignore symbol keys and will copy all properties from the object.)

To enhance this idea, one could devise a function that adds a property with a unique symbol key to an object. The addPropertyBySymbol function below demonstrates this.

const user = {

name: "witch",

nickname: "witch",

position: "developer",

age: 25

}

const isWorking = Symbol("isWorking");

function addPropertyBySymbol(obj) {

obj[isWorking] = true;

}

addPropertyBySymbol(user);

// Based on whether the user object holds the isWorking symbol

if (user[isWorking]) {

console.log("isWorking exists");

}

Furthermore, a constructor can be designed to automatically add hidden properties when creating instances. While the following code uses the constructor's prototype property, a similar effect can be achieved using class syntax in the constructor method.

function Person(age) {

this.age = age;

}

Person.prototype[isWorking] = function() {

return this.age > 18;

};

const person = new Person(25);

console.log(person[isWorking]()); // true

By adding hidden properties in this manner, one can make decisions about specific objects or instances easily and utilize those properties for identification without fearing conflicts with existing code, external library code, or any future additions.

4.3. Comparison with Other Methods

As noted earlier, such hidden properties can be utilized to create properties that cannot be interfered with by other code, or to generate identifiable values similar to pop-ups or alerts.

let id1 = Symbol("id");

let id2 = Symbol("id");

let cafe1 = {

name: "Starbucks",

[id1]: 1,

};

let cafe2 = {

name: "EDIYA",

[id2]: 2,

};

But is it absolutely necessary to do it this way? Libraries like uuid already exist that easily provide such functionality. Using UUID, we could write the code as follows:

const { v4: uuidv4 } = require("uuid");

const id = uuidv4();

function addPropertyByRandom(obj) {

obj[id] = 1;

}

let user = {

name: "Kim Sung-hyun",

};

addPropertyByRandom(user);

if (user[id]) {

console.log("id exists");

}

While this behavior is largely similar, UUID libraries are not particularly large and won’t significantly increase bundle sizes. Alternatively, one can use crypto.randomUUID() in modern browsers to avoid libraries altogether.

While the choice between using a library or not may not be crucial, I'll employ the well-known UUID library in the example.

However, there’s a drawback to random string generation methods: they are often too easily accessible from outside. While symbols are not completely private, they do provide a greater degree of security against common property access methods such as for..in, JSON.stringify, or Object.keys().

Consider the following code: properties defined through symbols remain hidden from typical access methods, while properties using random strings may be exposed.

const { v4: uuidv4 } = require("uuid");

const id = uuidv4();

const symbolId = Symbol("id");

function addPropertyByRandom(obj) {

obj[id] = 1;

}

function addPropertyBySymbol(obj) {

obj[symbolId] = 1;

}

let user1 = {

name: "Kim Sung-hyun",

};

let user2 = {

name: "Witch",

};

addPropertyByRandom(user1);

addPropertyBySymbol(user2);

// {"name":"Kim Sung-hyun","8f2aeb41-eb10-43f0-944d-fd994926b63e":1}

// Random string changes every time

console.log(JSON.stringify(user1));

// {"name":"Witch"}

console.log(JSON.stringify(user2));

// name and random string are printed

for (let i in user1) {

console.log(i);

}

// Only name is printed

for (let i in user2) {

console.log(i);

}

Of course, it’s possible to obscure random string properties from user access through Object.defineProperty. For example, the addPropertyByRandom function above can be modified as shown below to achieve a similar effect with random strings.

function addPropertyByRandom(obj) {

Object.defineProperty(obj, id, {

enumerable: false,

value: uuidv4(),

});

}

However, in an environment that supports symbols, using them is a more straightforward and safer option than dealing with potential collisions in random string creation or the complexities of Object.defineProperty.

5. Well-known Symbols

5.1. Background

Before symbols were introduced, JS employed object internal function properties for several built-in operations. For instance, the JSON.stringify function still uses an object's toJSON() method. A method like toString() was also defined as a typical object property.

However, as these object internal function properties continued to grow, the risk of breaking backward compatibility due to name collisions increased. This has complicated developers’ considerations regarding the properties they create.

By mapping these built-in functions to symbol keys, such issues can be ameliorated. The symbols used in this capacity are referred to as well-known symbols.

5.2. Introduction to Well-known Symbols

The static properties of the Symbol constructor function are all symbols in their own right. These symbols are termed well-known symbols and behave as a type of protocol within JavaScript's built-in operations.

Typically, these well-known symbols are distinguished by prefixing them with @@, such as @@toPrimitive. This distinction arises from the fact that symbols do not have literals, and one can reference the same symbol by different aliases, such as Symbol.toPrimitive.

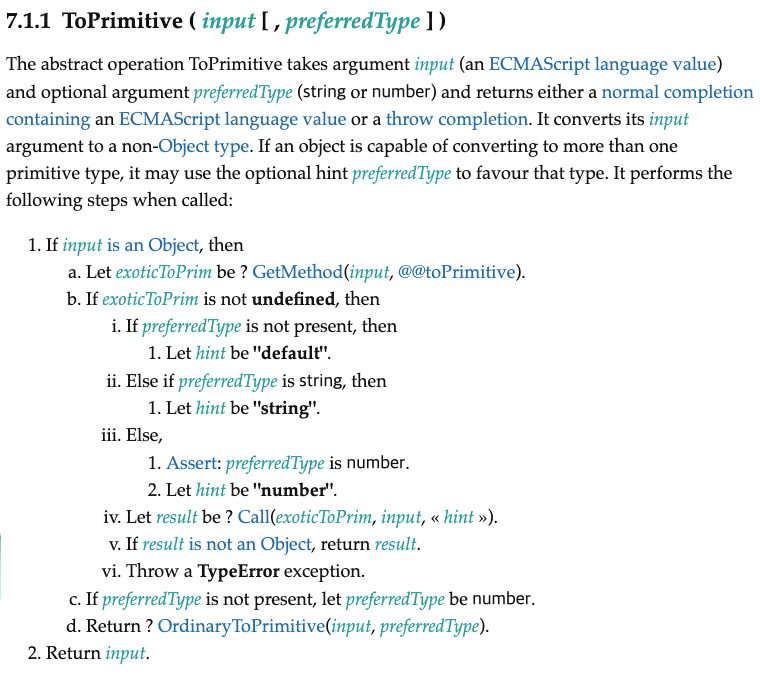

For instance, when reading the ECMA specification for JS, you’ll repeatedly encounter the built-in operation ‘ToPrimitive’. This operation is utilized for converting objects to primitive types, where the method @@toPrimitive is used primarily. If this method does not exist on an object, toString and valueOf will be used.

Other well-known symbols include @@iterator and @@toStringTag. JavaScript prioritizes the use of well-known symbols for its built-in operations, and in the next section, we'll explore several representative well-known symbols. It’s important to note that this article focuses more on the concept of symbols rather than specific well-known symbols.

Additionally, well-known symbols are guaranteed to remain unique throughout the lifespan of a program, alleviating concerns related to garbage collection. They exist continuously.

6. Examples of Well-known Symbols

JavaScript features the following well-known symbols.

6.1. Symbol.unscopables

This symbol excludes specific properties of an object from being bound in with statements, created to resolve conflicts arising from such statements.

Using Symbol.unscopables allows one to hide an object's conventional properties from with bindings like this:

const human = {

name: 'John',

age: 30,

[Symbol.unscopables]: {

age: true

}

};

with(human) {

console.log(age); // Uncaught ReferenceError: age is not defined

}

When the names of existing properties or methods in an object collide with names in with bindings, this @@unscopables can be employed to obscure the original properties.

6.2. Symbol.toPrimitive

This method is used when converting an object to a primitive type, allowing for different primitive types to be returned based on the hint provided. However, there are no strict limits; it simply needs to return a primitive value.

const user = {

name: "Kim Sung-hyun",

age: 30,

// Method for converting to primitive.

// It can return as different primitive types based on the hint provided.

// But as long as the return type is a primitive, there are no constraints.

[Symbol.toPrimitive](hint) {

return this.age;

},

};

console.log(String(user)); // 30

// Convert to number

console.log(+user); // 30

Built-in objects like Date have this custom toPrimitive method.

6.3. Symbol.toStringTag

In ECMA5, every object possessed an internal property [[Class]] that designated the classification of the object and was utilized in the toString() method.

However, since ES6 this [[Class]] property has been removed, and for compatibility, @@toStringTag was introduced. Thus, by overloading @@toStringTag in a class, it will be used upon calling the toString() method.

class MyClass {

get [Symbol.toStringTag]() {

return 'My Class';

}

}

const myClass = new MyClass();

console.log(myClass.toString()); // [object My Class]

Further details on the operation of toString() can be found in related articles.

6.4. Symbol.iterator

The for..of loop begins by calling obj[Symbol.iterator](). Thus, by utilizing the Symbol.iterator method, iteration can be overloaded.

6.4.1. Iterator Protocol

In this case, the function responsible for iteration adheres to the iterator protocol, requiring the object to have a next method adhering to the specific rules.

The next method must return an object with two properties:

- done (boolean): Indicating whether the iterator has completed its last iteration (true) or if there are still tasks pending (false). If the iterator has a return value, this will set the value.

- value: A JavaScript value returned from the iterator. It can be omitted if 'done' is true.

This can be observed through the inherent iterator for strings.

let word = "witch";

let it = word[Symbol.iterator]();

// {value: 'w', done: false}

console.log(it.next());

// {value: 'i', done: false}

console.log(it.next());

By overloading Symbol.iterator, one can alter the iteration functionality. In the following code, the Symbol.iterator of the user object is overloaded, resulting in strings that differ from the name when traversed using for..of.

let user = {

name: "witch",

[Symbol.iterator]: function () {

return {

next: function () {

if (this._first) {

this._first = false;

return { value: "work", done: false };

} else {

return { done: true };

}

},

_first: true,

};

},

};

let it = user[Symbol.iterator]();

// {value: 'work', done: false}

console.log(it.next());

// {done: true}

console.log(it.next());

// "work" is displayed due to the usage of Symbol.iterator.

for (let i of user) {

console.log(i);

}

6.4.2. Creating Generators

Generators allow for simplified sequential access to complex data structures. They enable values to be returned one at a time according to necessity.

Generators are functions that can pause execution and return to a previous state when invoked. They can yield multiple values in a single call.

The following code illustrates that each call to the next method retrieves a yielded value from the getStudyMember function. This is particularly useful when dealing with extensive information that must be accessed in parts.

function* getStudyMember() {

yield "Member AAA";

yield "Member BBB";

yield "Member CCC";

yield "Member DDD";

yield "Member EEE";

yield "Member FFF";

}

const member = getStudyMember();

console.log(member.next());

console.log(member.next());

console.log(member.next());

console.log(member.next());

Once created, this generator can be utilized as an iterable object. Both spread, for..of, etc., are all applicable.

const member = getStudyMember();

// Names are printed one at a time

for (const m of member) {

console.log(m);

}

Using generators allows for the definition of access order for complex data structures, enabling sequential iteration over intertwined data to be managed much simply.

Moreover, when a generator is assigned to Symbol.iterator, that generator can treat complex objects as iterable, similar to arrays.

An example of this is demonstrated below, where members of a study group are nested within friendship hierarchies, allowing for easy traversal and sequencing based on the structure, facilitating functionality extension using well-known symbols.

function Study() {

this.members = {

name: "Member AAA",

friend: {

name: "Member BBB",

friend: {

name: "Member CCC",

friend: {

name: "Member DDD",

},

},

},

};

this[Symbol.iterator] = function* () {

let node = this.members;

while (node) {

yield node.name;

node = node.friend;

}

};

}

const myStudy = new Study();

for (let m of myStudy) {

console.log(m);

}

By employing such generators, the complexity of unique data structures may be abstracted away. This enables other developers to utilize the data structures I’ve created conveniently.

For further insights into the structure and internal workings of generators, you may refer to this article on concurrency in loops, which has a brief overview, among many other helpful articles.

6.5. Symbol.hasInstance

The instanceof operator checks whether an object is an instance of a particular class. The method invoked here is @@hasInstance, located in the prototype property of the class's constructor or function, which then returns the boolean result.

Thus, this behavior can be customized as per requirement. For example, by overloading the @@hasInstance method in the class constructor, instanceof can be instructed to behave as desired. The following code snippet will make MyClass regard all objects as instances:

class MyClass {

static [Symbol.hasInstance](obj) {

return true;

}

}

console.log({} instanceof MyClass); // true

console.log(1 instanceof MyClass); // true

console.log('foo' instanceof MyClass); // true

Other well-known symbols exist; for a complete list, refer to articles from Developer's Archive or MDN documentation.

6.6. Characteristics of Well-known Symbols

Well-known symbols are shared across every engine context. They operate similarly to the symbols found in the global symbol registry. However, despite having similar sharing characteristics, well-known symbols cannot be located in the global symbol registry.

7. Conclusion

The symbol, a primitive introduced in ES6, is a value that is unique and does not duplicate with other values. Therefore, when using symbols as keys, the risk of property collisions is eliminated, underpinning the functionality of various internal object implementations.

However, the unique nature of symbols and their capability to offer a degree of attribute hiding are not compelling enough to warrant frequent application-level usage. In fact, with the popularity of TypeScript supporting enum, the scenarios where symbols might be applied have diminished.

At the application level, it may help to consider symbols as an option to create hidden properties or enum-like constructs, taking into account potential name collision issues. However, in JS internal implementations and library creation, symbols are a valuable asset.

References

MDN's symbol documentation: https://developer.mozilla.org/ko/docs/Web/JavaScript/Reference/Global_Objects/Symbol

Modern JavaScript Tutorial's symbol section: https://ko.javascript.info/symbol

NHN Cloud, Recent Updates on JavaScript Symbol: https://meetup.nhncloud.com/posts/312

Articles on using symbols: https://medium.com/intrinsic-blog/javascript-symbols-but-why-6b02768f4a5c

Another article on symbol usage: https://roseline.oopy.io/dev/javascript-back-to-the-basic/symbol-usage

http://hacks.mozilla.or.kr/2015/09/es6-in-depth-symbols/

Reference for Symbol.iterator: https://valuefactory.tistory.com/279

"JavaScript Coding Technique", Chapter 41, 'Generate Iterable Properties with Generators'

Symbol.species: https://www.bsidesoft.com/5370

The original purpose of symbols: https://exploringjs.com/es6/ch_symbols.html#_can-i-use-symbols-to-define-private-properties

Symbol.species symbols and their uses: https://jake-seo-dev.tistory.com/333

crypto.randomUUID: https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/API/Crypto/randomUUID

"JavaScript Symbols: the Most Misunderstood Feature of the Language?": https://blog.bitsrc.io/javascript-symbols-the-most-misunderstood-feature-of-the-language-282b6e2a220e

ECMAScript 6 Symbols and Symbol Properties: https://infoscis.github.io/2018/01/27/ecmascript-6-symbols-and-symbol-properties/