Operating System Dinosaur Book Chapter 4 Summary

This summarizes Chapter 4 of the Operating System, focusing on threads and concurrency.

1. Thread

Consider a single process having only one execution flow. Then, one application must create multiple processes. For example, one process related to a web browser might render webpages while another fetches data from the network.

However, dividing an application into multiple processes is inefficient. This increases the number of process creations, results in more context switching, and increases inter-process communication. Therefore, the operating system introduced the concept of threads to allow multiple execution flows within a process.

1.1 Concept of Thread

A thread can be considered the basic unit of CPU utilization. It is essentially an execution flow consisting of a thread ID (tid), individual program counter, set of registers, and stack. Multiple threads can exist within a process, sharing operating system resources like code and data areas with other threads of the same process.

In other words, a process can have multiple execution flows (threads). The advantages of multithreaded programming are as follows:

- Multiple execution flows can operate simultaneously, providing more immediate responses to users in interactive programs.

- Threads share resources within a process, making them easier to share compared to processes.

- Creating threads and switching flows between them incurs significantly lower costs than working with processes.

- In multiprocessor systems, threads can be executed in parallel on different processors.

1.2 Multicore Programming

Modern computer systems are equipped with multiple cores on a single computing chip, and the operating system recognizes each core as a CPU. In such a multicore system, a process can be divided into multiple threads, each executed simultaneously on different cores, meaning some threads can actually run at the same time in parallel.

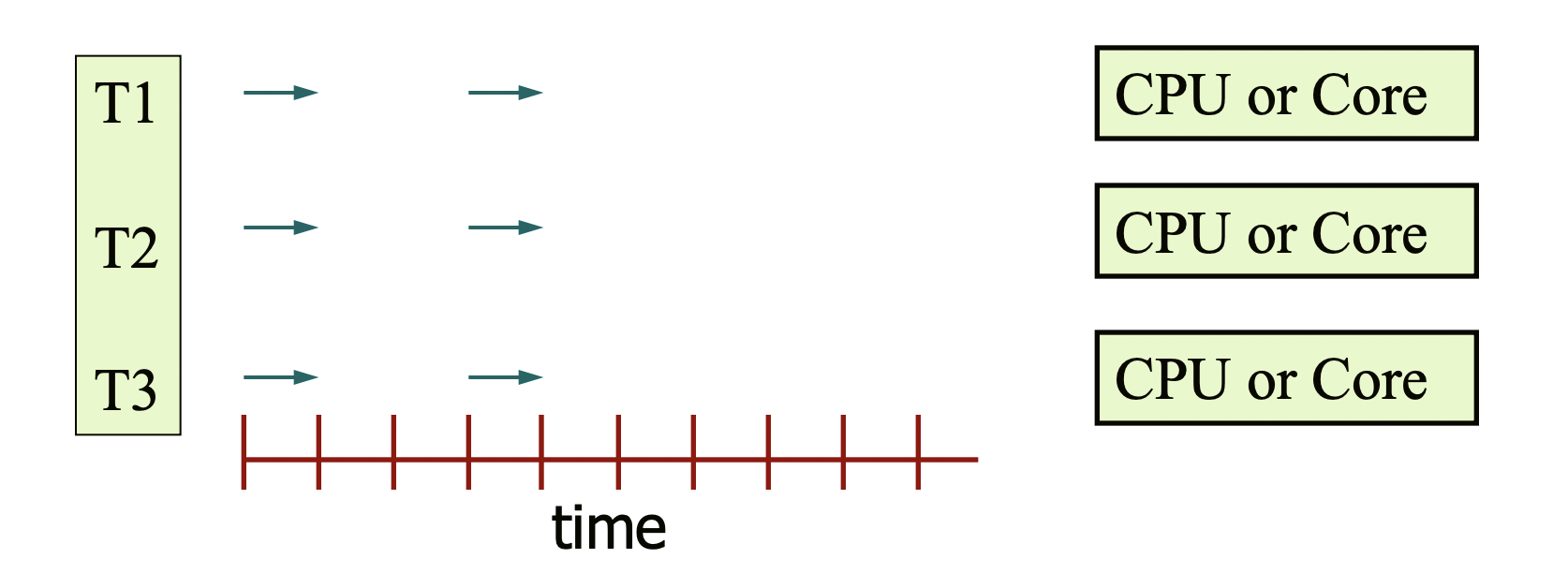

This brings up the distinction between concurrency and parallelism. Parallelism refers to using multiple cores (or CPUs) to execute multiple threads simultaneously. The image below shows multiple threads genuinely progressing together.

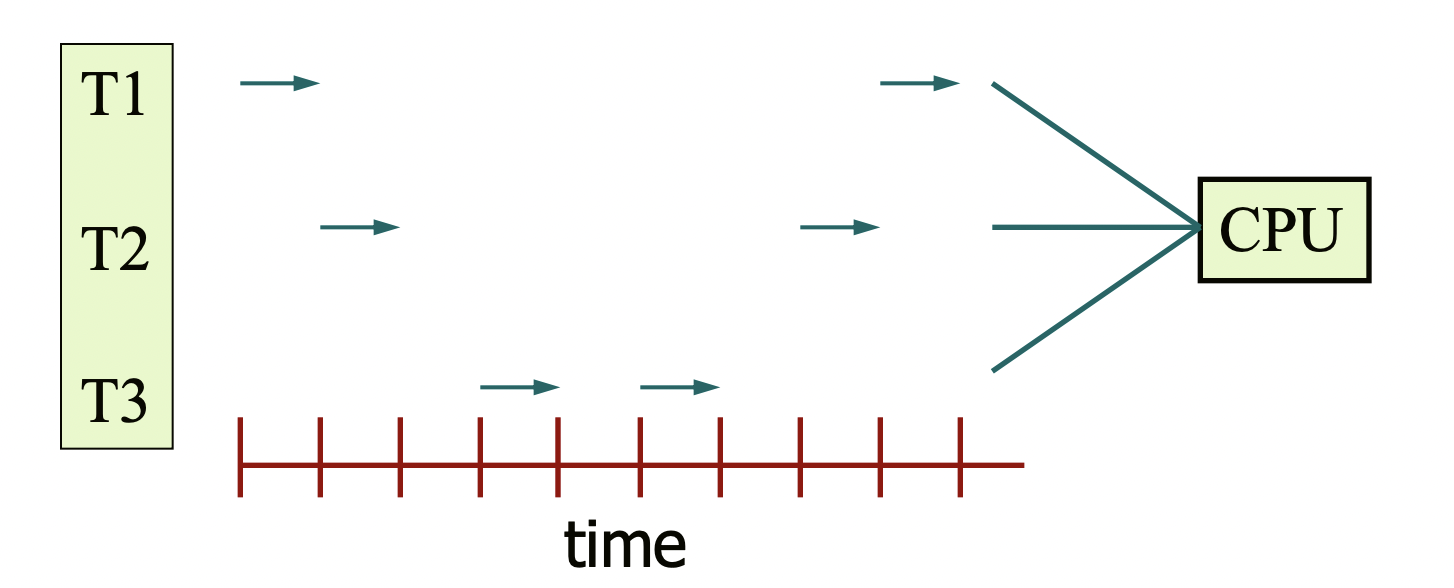

However, even with a single core, multiple tasks can progress concurrently. By rapidly switching between several threads on a single processor, the user can perceive that multiple tasks are running simultaneously. This is called concurrency.

The next image illustrates concurrency where only one CPU is present, and three threads take turns executing. Hence, concurrency is possible even without parallelism.

What advantages does achieving concurrency with a single CPU bring? It may seem there are none, but it does speed up computation. When a thread is blocked due to I/O operations, other threads can continue processing, thereby enhancing overall efficiency even with a single processor.

However, parallel programming is challenging. Firstly, the program must be analyzed to divide its execution into independent parallelizable tasks. Next, those tasks must be evenly distributed across cores, and the data accessed by each task must be independently divided. Lastly, the tasks should not depend on each other. If these conditions are met, parallel programming can be accomplished, although it is harder to debug than traditional single-threaded programming.

2. Multithreading Model

2.1 Types of Threads

Threads can be classified into user threads and kernel threads.

2.1.1 User Thread

User threads are provided in user space and managed without kernel support, typically through a thread library. Since everything occurs in user space, there is no need for the operating system to support threads, and context switching does not occur in the OS scheduler. Additionally, since there are no kernel calls, there is less overhead during interrupts compared to kernel threads.

2.1.2 Kernel Thread

Kernel threads operate at the kernel level and are managed directly by the kernel, making them dependent on the kernel. However, this dependence has its advantages, as the kernel can manage each thread individually, providing stability and various features.

The downside is frequent switching between user mode and kernel mode can lead to performance degradation, and the implementation is more complex. They also tend to consume more resources due to heavy operations when calling the kernel for scheduling or synchronization.

However, the number of kernel threads ultimately determines the performance of parallelism since it is the kernel threads that handle computations in a multithreaded environment.

2.2 Thread Mapping Model

While user threads and kernel threads exist, a significant relationship must exist between them in a multithreaded environment. In a non-multithreaded environment, user-level threads could simply execute on processors without needing mapping.

However, since most operating systems today are multithreaded, user thread-kernel thread mapping is crucial. There are many-to-one, one-to-one, and many-to-many models.

2.2.1 Many-to-One Model

In the many-to-one model, multiple user threads are mapped to a single kernel thread, managed by the user space thread library.

The issue is that if one thread makes a blocking system call, the sole kernel thread gets blocked, causing all other threads to block as well (blocking problem). This model does not efficiently utilize multiprocessor or multicore environments.

Only one thread can access the kernel at a time, meaning the actual flow of operations is limited to one (even if numerous tasks run on user threads, the actual operations happen at the kernel level).

2.2.2 One-to-One Model

In the one-to-one model, each user thread maps to one kernel thread. If one thread makes a blocking system call, other kernel threads can still process operations, yielding higher parallelism.

Creating a user thread requires creating a kernel thread, which increases overhead as the number of kernel threads rises. Windows and Linux operate using this model.

2.2.3 Many-to-Many Model

The many-to-many model maps multiple user threads to a lesser or equal number of kernel threads, with the number of kernel threads varying based on devices or applications.

In this model, users can create as many user threads as desired. Corresponding kernel threads can operate in parallel, and even if one thread calls a blocking system call, other kernel threads can continue processing.

Thus, in the many-to-many model, users can generate any desired number of user threads, and the operating system creates several kernel threads to manage them accordingly.

2.2.4 Two-Level Model

This is a variation of the many-to-many model, still mapping N user threads to a lesser or equal number of kernel threads. However, it offers 1-1 mapping for specific user threads, which is beneficial for handling threads that need quicker processing or have high utilization.

While the many-to-many model appears ideal, its implementation can be complex. Moreover, as most systems possess numerous cores, limiting the number of kernel threads becomes less critical. Therefore, most operating systems, including Windows and Linux, adopt the one-to-one model.

2.3 Threads and Cores

How do user threads and kernel threads interact? In systems adopting the many-to-many model, most place an intermediary data structure between user threads and kernel threads. This intermediary is a virtual processor (also known as LightWeight Processor, LWP).

In any case, the user thread library selects which user thread will execute, forming the LWP for user-level scheduling. Each LWP maps to one kernel thread.

Simply put, when the user thread library allocates tasks to threads, the library schedules them and constructs the LWP. The kernel then uses the LWPs to schedule tasks to physical cores.

Thus, true parallelism is not achieved by having multiple user threads but rather by having multiple physical cores. True parallelism can be realized when threads and cores have a 1:1 correspondence.

3. Thread Pool

Creating a thread for each request and eliminating it once the request is completed is more efficient than doing so for processes, but it still incurs costs. One solution is the thread pool. Upon starting a process, a certain number of threads are created and pooled, allocating threads from this pool as requests arrive.

If no threads are available in the pool, the tasks will wait until a thread becomes available. Upon completing a request, the thread returns to the pool in a reusable state.

This approach allows existing threads to be used faster than creating new threads to respond to requests, thus enhancing threading efficiency. Additionally, there can be a limit on the number of threads since the number cannot exceed the pool's size.

4. Issues Related to Threads

4.1 fork, exec System Call

In a multithreaded environment, a problem arises with fork. If a thread in one program calls fork, should the new process replicate only the thread that invoked fork, or should all threads be replicated?

This depends on exec. If exec is executed after fork, the child process will be replaced with the program passed as a parameter to exec, thus negating the need to replicate all threads (only the thread that called fork needs to be replicated).

However, if exec is not called after fork, all threads must be copied. Some Unix variants support both kinds of fork (one that copies all threads and one that only copies the calling thread).

4.2 Signals

Signals are used in Unix systems to notify when specific events occur. Signals can be synchronous or asynchronous. The distinction is as follows:

-

Synchronous signals: Signals transmitted to the same process that performed the operation causing the signal, such as unauthorized memory access or division by zero.

-

Asynchronous signals: Signals generated from external sources while a process is running. These can be from keypresses like Ctrl+C that stop a process, timer expirations, or process terminations via the kill command. It is natural for a signal terminating process A to come from outside process A.

However, issues arise in how to handle these signals. If a process has only one thread, the solution is straightforward: simply deliver the signal to that process. Since there will only be one thread to receive the signal, it simplifies handling.

The problem arises when a process has multiple threads. If a process receives a signal, which thread within that process should the signal be sent to? The following options exist:

- Send the signal to the thread it applies to.

- Send the signal to all threads within the process.

- Send the signal to a selection of threads.

- Designate a specific thread to receive all signals.

4.3 Thread Cancellation

There may be instances where a thread is forcibly terminated before it finishes execution. This target thread is referred to as the "target thread." There are two methods for canceling a thread:

-

Asynchronous cancellation: The target thread is immediately terminated. For example, pthreads provides a function pthread_cancel(tid) that immediately terminates the thread. The issue is that resources allocated to the target thread may not be fully reclaimed.

-

Deferred cancellation: The target thread periodically checks whether it should terminate. If termination is required, it proceeds to do so. For instance, the pthreads API offers a function named pthread_testcancel which cancels the thread if it identifies a pending cancellation request.

4.4 Thread Local Storage (TLS)

TLS is a data area exclusive to each thread that only it can access. Unlike a local variable confined to a single function, TLS persists throughout the entire function call.

For example, consider a function A that increments a specific variable in TLS by one. If the TLS variable starts at 0 every time function A runs, it will behave as 1, 2, 3, and so on. However, the variable in other threads remains 0.

References

Regarding user threads and kernel threads: https://www.crocus.co.kr/1255