Operating System Dinosaur Book Chapter 6 Summary

This document summarizes Chapter 6 of the operating system, focusing on synchronization tools.

1. Background of Synchronization Tools

Previously, we discussed methods by which processes can interact, namely through shared data and message passing. However, using shared data can lead to synchronization issues. For instance, if process A is writing to shared data and process B also attempts to write to the same data, it becomes uncertain which data will be reflected in the shared data.

When multiple processes access and manipulate the same data, and the outcome depends on the specific order of access or which process finishes first, this situation is referred to as a race condition. To address such issues, synchronization is necessary.

Synchronization requires atomic operations, meaning that during the execution of an operation, no other processes can execute that operation. For example, if writing to shared data is atomic, another process cannot attempt to write to that shared data while one process is performing the write operation.

As multi-threaded environments become more common, the likelihood of synchronization issues has increased, further heightening the need for synchronization tools.

2. Critical Section Problem

The critical section refers to the code that accesses shared data that should not be accessed simultaneously by two or more processes. Thus, while one process is executing in the critical section, other processes should not access that critical section.

The critical section problem entails designing a protocol that processes can use to synchronize their activities, ensuring that only one process executes in the critical section at a time.

2.1 Conditions for the Solution

There are various methods to solve the critical section problem, but any solution must meet the following conditions:

- Mutual exclusion: Only one process can access the critical section at a time.

- Progress: If no process is executing in its critical section, and some processes wish to enter their critical section, then the selection of the process that gets to enter cannot be postponed indefinitely; it must eventually be allowed.

- Bounded waiting: Once a specific process has requested entry to the critical section, there must be a limit on how many other processes can enter their critical section before it is granted access.

2.2 Terminology

Relevant terms associated with the critical section are defined as follows:

- Entry section: Each process requests permission to enter its critical section. The section where this request is made is called the entry section.

- Exit section: The part where a process leaves the critical section after execution is referred to as the exit section.

- Remainder section: The portion excluding the entry section, critical section, and exit section is referred to as the remainder section.

A typical structure of a process is illustrated below.

while(true){

entry section;

critical section;

exit section;

remainder section;

}

2.3 Possible Solutions

One potential solution is Peterson's Algorithm, but we will first consider simpler solutions.

Assuming there are only two processes, P0 and P1, we might consider the following approach.

2.3.1 First Attempt

Introducing a variable called turn, initially set to turn=0, we will assume that if turn==i, process Pi (i-th process) can enter the critical section. The implementation in process i can be written as follows.

do{

while(turn != i);

// critical section

turn = j;

// remainder section

}while(1);

Process 0 starts and performs work in the critical section, then hands over the critical section to the other process (in this case, only process 1). This approach seems to work correctly.

However, it violates the progress condition. If turn==0 and P1 becomes ready to enter the critical section, because turn!=1, P1 will continuously loop through the while statement and will not be able to enter the critical section.

2.3.2 Second Attempt

Declare a boolean flag[N] array with as many elements as there are processes. In this case, flag[2]. Initially, all values are set to false. Let's assume flag[i] being true indicates that process i is ready. The implementation in process i can be represented as:

do{

flag[i] = true;

while(flag[j]);

// critical section

flag[i] = false;

// remainder section

}while(1);

This code satisfies mutual exclusion but also fails to meet progress. If flag[0] becomes true in P0 and prior to entering the critical section P1 also sets flag[1] to true, then both P0 and P1 will wait indefinitely while no process is in the critical section.

2.3.3 Third Attempt (Peterson's Algorithm)

Using both turn and flag, we assume turn==i means process i can enter the critical section, while flag[i] being true indicates process i is ready. The implementation for process i can be written as follows.

do{

flag[i] = true;

turn = j;

while(flag[j] && turn == j);

// critical section

flag[i] = false;

// remainder section

}while(1);

Process i first sets flag[i] to true and assigns turn to j. If process j becomes ready, the system allows it to enter.

Even if both processes wish to enter at the same time, the value of turn will ultimately decide which process enters the critical section.

This approach satisfies all previous three conditions, but on modern computer architectures, compilers may reorder independent read/write operations, causing Peterson's Algorithm to not function correctly on contemporary systems.

Another mutual exclusion algorithm, Dekker's Algorithm, also exists. For further interest, please refer to the following links: Peterson's Algorithm, Dekker's Algorithm difference, Dekker's Algorithm on Crocus Blog.

However, all previously examined algorithms cannot guarantee performance on modern computer architectures. Therefore, we need to utilize appropriate synchronization tools, which range from hardware support to high-level APIs. Let’s examine them one by one.

3. Hardware Support for Synchronization

3.1 Memory Barrier

The issue with Peterson’s Algorithm lies in the potential reordering of instructions by the system; that is to say, changes made in one process's memory may not be immediately reflected in another process. To address this, a hardware-supported synchronization feature called a Memory Barrier is employed.

The Memory Barrier instruction ensures that the load and store operations that follow it are executed only after the current process has completed its store operation in memory. Consequently, subsequent load and store operations will read or write the most recent values reflected in memory.

In other words, it synchronizes the memory so that changes from one processor are visible to all other processors.

3.2 Hardware Instructions

Modern systems provide special hardware instructions that execute operations atomically without interruption. These instructions can simplify the resolution of critical section issues. Typically, locks are manipulated using instructions such as TestAndSet and Swap.

These instructions are provided in C++'s atomic header, which offers atomic variables and flag types. Functions such as atomic_flag_test_and_set are available. Acknowledgements to the source.

3.2.1 Test and Set

The TestAndSet instruction checks and modifies the content of one word atomically.

// The following operation is performed atomically.

int TestAndSet(int *target) {

int rv = *target;

*target = TRUE;

return rv;

}

The key point is that this instruction executes atomically. Therefore, implementing a lock using TestAndSet allows for easy mutual exclusion.

do{

while(TestAndSet(&lock));

// critical section

lock = FALSE;

// remainder section

} while(TRUE);

After finishing access to the critical section, the lock variable is set to FALSE, allowing other processes to gain access. However, if the lock variable is TRUE, processes will continue to wait, meaning bounded waiting is not satisfied.

3.2.2 Swap

The Swap instruction exchanges the contents of two words.

void Swap(bool *x, bool *y) {

bool tmp = *x;

*x = *y;

*y = tmp;

}

Mutual exclusion can also be implemented by manipulating locks through the Swap instruction as follows.

// lock is initially set to false.

do{

key=TRUE;

while(key==TRUE){

Swap(&key, &lock);

}

// critical section

lock=FALSE;

// remainder section

} while(TRUE);

In this case, like the previous implementation, if the lock variable is TRUE, the process will continue to wait, thus not satisfying bounded waiting. To meet the bounded waiting criteria, the following implementation uses a waiting array.

The initial values of the waiting array and lock variable should both be set to FALSE. The following code runs in process i.

do{

waiting[i]=TRUE; key=TRUE;

while(waiting[i]==TRUE && key==TRUE){

Swap(&key, &lock);

}

waiting[i]=FALSE;

// critical section

j=(i+1)%n;

while(j!=i && waiting[j]==FALSE) j=(j+1)%n;

if(j==i) lock=FALSE;

else waiting[j]=FALSE;

// remainder section

} while(TRUE);

The process enters the critical section when either waiting[i]==FALSE or key==FALSE. The key can only become FALSE via the Swap instruction, and waiting[i] can only become FALSE when another process exits the critical section, ensuring that only one process can have waiting[i] FALSE at any one time.

The line of code:

while(j!=i && waiting[j]==FALSE) j=(j+1)%n;

This code runs when one process exits the critical section, searching through the waiting array for the first process that is waiting (whose waiting is TRUE) and setting it to FALSE to allow that process to enter the critical section.

Thus, a process wishing to enter the critical section will eventually do so within n cycles, thereby ensuring bounded waiting.

3.3 Atomic Variable

Some systems provide atomic variables that allow for atomic operations. Operations involving these variables are performed atomically.

However, they are generally used more to guarantee the atomic update of a single piece of shared data rather than to solve critical section issues.

4. Software Tools

4.1 Mutex Lock

More abstract software tools exist to address the critical section problem. The simplest tool is the mutex lock, which stands for mutual exclusion.

Processes acquire a lock when trying to enter the critical section and release the lock upon exiting. Both operations must be performed atomically.

Let's assume we have functions acquire and release implemented as follows.

acquire(){

while(available==FALSE); // busy waiting

available=FALSE;

}

release(){

available=TRUE;

}

If another process occupies the critical section, any other processes attempting to enter will continuously call acquire, causing them to spin in busy waiting.

Such locks that engage in busy waiting are referred to as spin locks because the process keeps spinning until it can acquire the lock. Although this may waste processing capability that could be utilized productively by other processes, the advantage is that once a process is able to enter the critical section, it can do so without a context switch.

Spin locks are often used when the duration of lock retention is expected to be short and in multi-processor systems.

4.2 Semaphore

Semaphores, while similar to mutexes, do not require busy waiting.

A semaphore S is an integer variable that can only be accessed through two atomic operations: wait and signal.

wait(S){

while(S<=0); // busy waiting

S--;

}

signal(S){

S++;

}

The semaphore was devised by Dutchman Edsger Dijkstra. Thus, the operation wait is sometimes referred to as P(S), derived from the Dutch word Proberen (to test), while signal is denoted as V(S), from Verhogen (to increment).

4.2.1 Types of Semaphore

Counting semaphores have no limit on the values they can hold. These semaphores can be used to limit the number of processes that can enter a critical section.

Binary semaphores only hold values of 0 or 1. They are simpler to implement than counting semaphores and function similar to mutex locks.

4.2.2 Utilization of Semaphores

Consider a scenario where N processes are competing for access to a critical section. In this case, an initial mutex semaphore with a value of 1 can be employed.

do{

wait(mutex); // wait if mutex<=0

// critical section

signal(mutex); // mutex++

// remainder section

} while(1);

Semaphores can also be used for more general synchronization problems. For instance, if process i's task A needs to be completed before process j's task B begins, we can use a flag semaphore initialized to 0.

Pi{

...

A_task

signal(flag); // Only makes the flag usable after A_task completes.

}

Pj{

...

wait(flag); // Wait until flag becomes 1 before starting B_task.

B_task

}

More specific implementations of semaphores can be found on this blog: Rebro's Blog.

5. Monitor

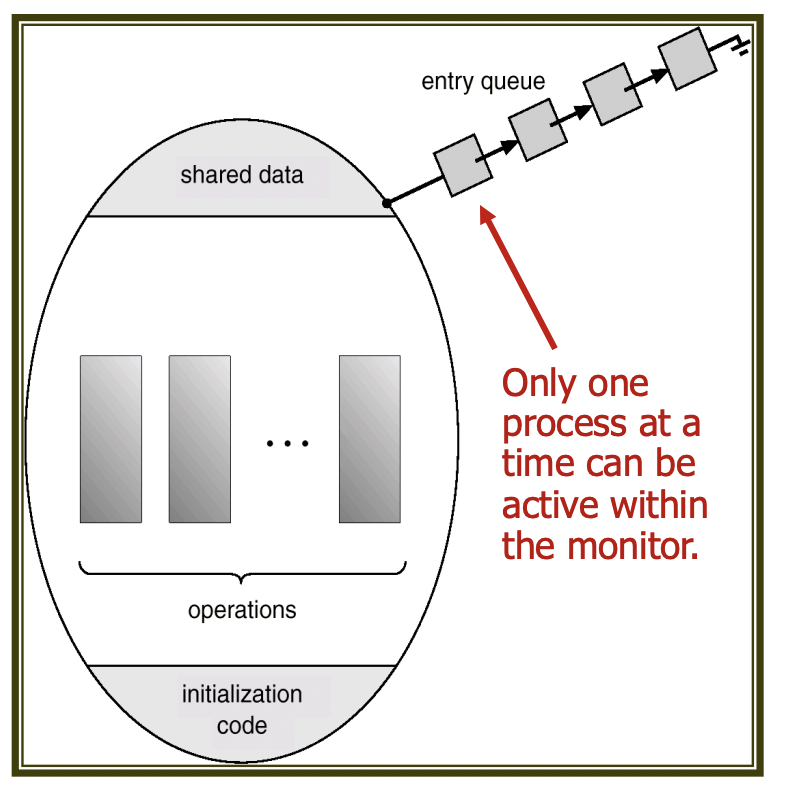

While mutex locks or semaphores can effectively solve the critical section problem, programmer errors can easily lead to mistakes. To mitigate this, monitors are used. Monitors guarantee safe shared access among concurrently executing processes by ensuring that only one process is active within the monitor at a time.

To facilitate the synchronization of processes within the monitor, a condition structure is provided that can be declared as condition x, y;.

Only two operations, wait and signal, are allowed for condition variables. For instance, a process that calls x.wait() will be paused until another process calls x.signal().

The invocation of x.signal() will resume only one of the paused processes. If no processes are paused, x.signal() will do nothing. The variables x and y function similarly to semaphores within the monitor, but unlike semaphore signal operations, there is the possibility that no action occurs.

5.1 Signal-related Issues in Monitors

Consider a process P within the monitor where x.signal() has been called. If there is another process Q that was paused by invoking x.wait(), and Q is the only process affected by x, then process P, which was already executing, must now reactivate Q. However, the monitor only permits one active process.

Two strategies are available:

- Signal and Wait: Process P will wait until Q exits the monitor, allowing P to continue upon Q's departure.

- Signal and Continue: Process Q will wait until P exits the monitor.

Given that P was already executing within the monitor, the signal and continue method seems more logical; hence, it is widely used in implementations such as pthreads.

However, the signal and continue approach may potentially alter some logical conditions that Q was waiting for when P becomes active, which provides signal and wait with its own advantages.

6. Liveness Problem

Liveness refers to a situation where processes will not wait indefinitely and will eventually perform some action. For example, a process that cannot execute due to an infinite loop is experiencing liveness failure. The following examples illustrate this:

6.1 Deadlock

Deadlock occurs when two or more processes are waiting indefinitely, where an event can only be triggered by one of those waiting processes.

Consider two processes, P0 and P1, accessing semaphores S and Q, initially set to 1.

P0

wait(S);

wait(Q);

...

signal(S);

signal(Q);

P1

wait(Q);

wait(S);

...

signal(Q);

signal(S);

P0 executes wait(S) while P1 executes wait(Q). For each to proceed, one must signal from the other process. This scenario exemplifies deadlock.

6.2 Starvation

Starvation is when a process is indefinitely blocked. It cannot be removed from the semaphores' waiting list and remains in a suspended state forever. For instance, if the highest priority process acquires the lock while continuously adding new processes to the lock’s waiting list, a lower-priority waiting process may end up waiting indefinitely—this is starvation.

6.3 Priority Inversion

This situation occurs when a high-priority process needs to access kernel data currently held by lower-priority processes, leading to scheduling difficulties.

For example, let processes A, B, and C have the priority order A<B<C, and C needs access to kernel data currently accessed by A. Since this kernel data is locked, C must wait until A completes its access.

If B subsequently preempts A, C will be forced to wait for B to finish, despite having a higher priority than B. This scenario illustrates priority inversion.

A is accessing data -> C is waiting for A -> B preempts A -> C is now waiting for A to finish by waiting on a lower-priority process B.

References

Blog by Park Seong-beom, summarizing Operating Systems in the Dinosaur Book Ch6: https://parksb.github.io/article/10.html

C++ atomic header reference page: https://en.cppreference.com/w/cpp/header/atomic