Sogang University Pintos - Project 1

1. Project Initialization

The goal of this assignment is to ensure that the system call handler and certain system calls function properly.

First, execute the make command in the src/userprog and src/examples directories within the pintos folder, and then execute the following command in the src/userprog directory.

pintos --filesys-size=2 -p ../examples/echo -a echo -- -f -q run 'echo x'

Ideally, executing echo x should output x, but currently nothing is printed. This is because the part that transfers the command to the operating system is missing.

The way commands are executed in Pintos is as follows: when a command like echo x is passed, echo and x are pushed onto the user stack, those arguments are then conveyed to the kernel, which executes the system call handler using those arguments. The system call handler then executes the appropriate system call.

However, since Pintos has not yet implemented the user stack, logic to transfer stack arguments to the kernel, or the system call handler, nothing is printed when echo x is executed. In other words, there is no connection between the user and the kernel (the appropriate system calls are already implemented in the kernel). In this project, we need to implement parts of this connection.

2. Argument Passing

2.1 Analysis

The user stack is the stack used by the user program and not the kernel. When a user program requests a system call from the kernel, it places the arguments in the user stack and transfers them. The kernel then retrieves the arguments from the user stack to execute the system call. This process of passing arguments from the user to the kernel is known as argument passing.

We need to implement the transfer of arguments to the user stack following the 80x86 calling convention. Where should this be implemented?

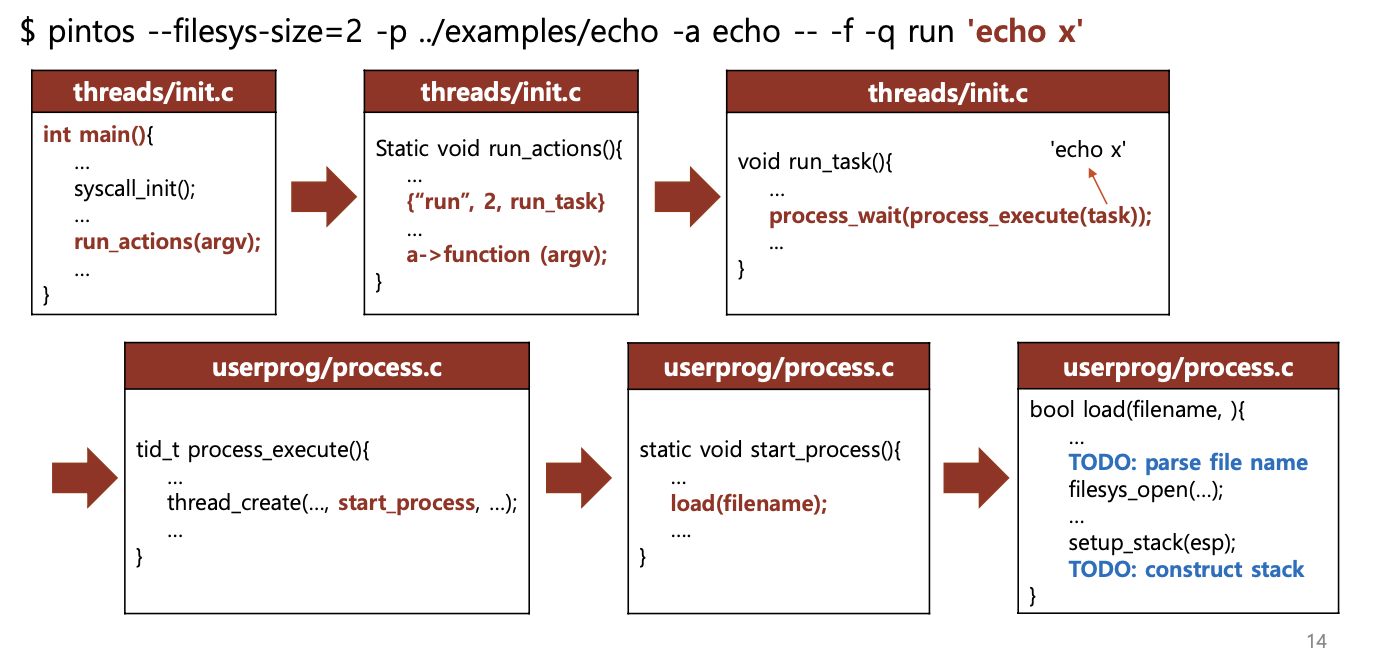

First, let's look into how Pintos executes programs. When the main function in threads/init.c runs, it calls the run_actions function. If the run option is provided, it in turn calls the run_task function, which creates a user process using process_execute. This newly created process enters process_wait, which means Pintos will wait for the user process to terminate (the process_wait part is not yet implemented, but that's the original plan).

How does this process creation happen? The process_execute function uses thread_create to create a new thread, which starts executing start_process before being queued.

The start_process function calls load to load the user program into memory (if loading fails, the thread ends). It then calls setup_stack to initialize the user stack. Therefore, we need to implement the pushing of arguments onto the user stack within the load function, after which it will be passed to the user program loaded in memory.

2.2 Modifying the Executable File Name

However, before proceeding, there is something to address. If we execute echo x as previously described, we get a load failed error (if it doesn't appear, replace the process_wait with a timer_msleep call; the load failed message will then be shown). The error message indicates that it failed to open a file named echo x... logically, the file containing the implementation for the echo command should be named echo, but we are incorrectly passing the entire command as the file name from the beginning. Let's fix that.

First, check what the file_name in the load function is. We can add a printf statement to output the file_name passed to load. However, since process_wait is not implemented yet, Pintos may exit before printing the result, so we temporarily replaced process_wait with a sleep of 2 seconds using the timer_msleep from src/devices/timer.h.

int process_wait (tid_t child_tid UNUSED) {

// timer_msleep waits in milliseconds.

timer_msleep(2000);

return -1;

}

Running the earlier command: pintos --filesys-size=2 -p ../examples/echo -a echo -- -f -q run 'echo x' confirms that the file_name argument now shows echo.

Here, the file_name gets passed as an argument to filesys_open. Thus, the file_name contents will open a file with that title. However, the file_name currently points to the entire command line. If the command is echo x, it recognizes echo x as the file name instead of just echo. Therefore, we need to modify the file_name to interpret just the first word separated by spaces as the file name. We can adjust the beginning of the load function to put the first word of file_name into a new variable file_name_first_word and pass it to filesys_open. Moreover, don't forget to free allocated memory.

/* Allocate and activate page directory. */

t->pagedir = pagedir_create ();

if (t->pagedir == NULL)

goto done;

process_activate ();

/* Parse the first word of file_name */

file_name_copy = malloc(sizeof(char) * (strlen(file_name) + 1));

strlcpy(file_name_copy, file_name, (strlen(file_name)));

file_name_copy[strlen(file_name)] = '\0';

file_name_first_word = strtok_r(file_name_copy, " ", &save_ptr);

printf("\n\n%s\n\n", file_name_first_word);

/* Open executable file. */

file = filesys_open(file_name_first_word);

if (file == NULL)

{

printf("load: %s: open failed\n", file_name_first_word);

free(file_name_copy);

goto done;

}

free(file_name_copy);

After recompiling in src/userprog and executing the command, we can confirm that file_name_first_word outputs echo. Although a page fault occurs, this will be resolved once we structure the user stack.

2.3 Structuring the User Stack According to Calling Conventions

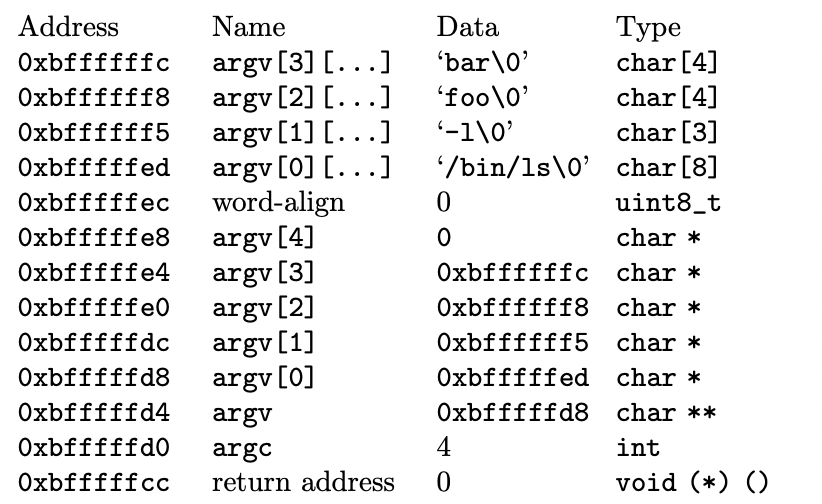

Now we need to structure the user stack according to the 80x86 calling convention. The details are well outlined in the Pintos Official Manual, pages 35-38.

For instance, consider the command:

/bin/ls -l foo bar

The calling convention indicates that it should be organized onto the stack as follows. Let's get started.

2.3.1 Putting Arguments on the Stack

This task uses the command line received and the stack pointer. We need to stack the command line arguments and addresses onto the user stack while manipulating the stack pointer (esp). Thus, we shall create a function construct_stack in src/userprog/process.c that takes both as parameters, along with the function prototype in src/userprog/process.h.

First, let's stack the arguments in string form onto the stack. Since we need to push them in reverse order, we need to know the total number of arguments. Thus, we will count the arguments first using the strtok_r function from <string.h>, which modifies the incoming string. Therefore, we should create a copy of the string.

void construct_stack(const char* file_name, void** esp) {

int argc, idx;

char** argv;

int total_arg_len, cur_arg_len;

char file_name_copy[1000];

char* file_name_token, *save_ptr;

strlcpy(file_name_copy, file_name, strlen(file_name) + 1);

}

Next, we will parse through the string to count the arguments. Any debugging output on the tokenized strings can be included as we implement the code.

argc = 0;

// Count arguments

// Function name parse

file_name_token = strtok_r(file_name_copy, " ", &save_ptr);

//printf("tokenized file name : %s\n", file_name_token);

// Count argument number

while (file_name_token != NULL) {

file_name_token = strtok_r(NULL, " ", &save_ptr);

//printf("tokenized file name : %s\n", file_name_token);

argc++;

}

//printf("arg count : %d\n\n", argc);

Next, we need to store the arguments (as strings) onto the stack. However, according to the calling convention, we must stack them in reverse order. Hence, we allocate space for the arguments and re-tokenize to store them while remembering the total length of the arguments for later.

argv = malloc(sizeof(char) * (argc + 1));

strlcpy(file_name_copy, file_name, strlen(file_name) + 1);

idx = 0;

total_arg_len = 0;

for (file_name_token = strtok_r(file_name_copy, " ", &save_ptr); file_name_token != NULL; file_name_token = strtok_r(NULL, " ", &save_ptr)) {

total_arg_len += strlen(file_name_token) + 1;

argv[idx] = file_name_token;

idx++;

}

Finally, we stack the arguments onto the user stack in reverse order while also saving the addresses of where each argument starts for future reference.

for (idx = argc - 1; idx >= 0; idx--) {

cur_arg_len = strlen(argv[idx]);

*esp -= cur_arg_len + 1; // include null character

strlcpy(*esp, argv[idx], cur_arg_len + 1);

// Save the starting address of each argument

argv[idx] = *esp;

//printf("file name token %s\n", *esp);

}

/* Word alignment */

if (total_arg_len % 4) {

*esp -= 4 - (total_arg_len % 4);

}

/* NULL pointer sentinel ensures that argv[argc] is NULL

(required by C standard) */

*esp -= 4;

**((uint32_t**)esp) = 0;

for (idx = argc - 1; idx >= 0; idx--) {

*esp -= 4;

**((uint32_t**)esp) = argv[idx];

}

//argv

*esp -= 4;

**((uint32_t**)esp) = *esp + 4;

//argc

*esp -= 4;

**((uint32_t**)esp) = argc;

//return address

*esp -= 4;

**((uint32_t**)esp) = 0;

free(argv);

}

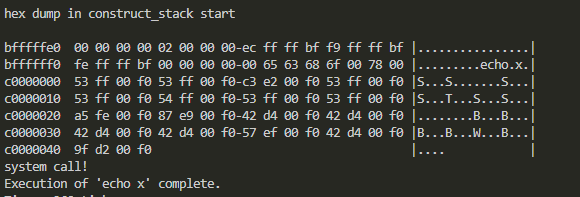

To verify the correct stacking of arguments, you may use the hex_dump function for debugging. Add the following code to the end of the construct_stack function.

printf("hex dump in construct_stack start\n\n");

hex_dump(*esp, *esp, 100, true);

In this state, compile in src/userprog and execute the command again to see the memory output in hexadecimal format. You can directly calculate and check whether the memory is organized according to the calling convention.

pintos --filesys-size=2 -p ../examples/echo -a echo -- -f -q run 'echo x'

3. System Call Handler

Now let's implement the system calls. Where should this be done? From the photograph captured earlier of hex_dump, after the result printed by hex_dump, you can see system call!. Let's find out where this print is implemented. It is located in src/userprog/syscall.c. The syscall_handler function there is responsible for printing system call!. So, what does this function do?

Referencing the resources at the bottom of the document, the main function in init.c calls write. This invokes the system call assembly function in src/lib/user/syscall.c, which pushes the system call number and arguments onto the user stack before calling the syscall handler.

At this point, the user stack is structured as follows:

Thus, the syscall number exists at the esp location, with the system call arguments stacked above it, at esp + 4, esp + 8, esp + 12, etc. This stack pointer esp is found within the esp of the intr_frame structure, which contains register information regarding the interrupt. Later, when returning a value from the system call, we will store it in the eax register from this structure.

Consequently, we need to write the part of the code that calls the appropriate system call based on the syscall number in esp. We reference src/lib/syscall-nr.h to understand which functions must be called for each syscall number. The comment /* Projects 2 and later. */ kindly informs us which system call numbers to use. Therefore, we will add the system call numbers in the system call handler using a switch statement, with the important note that esp in intr_frame is declared as a void pointer, requiring type conversion for dereferencing.

static void

syscall_handler (struct intr_frame *f UNUSED) {

switch (*(int32_t*)(f->esp)) {

case SYS_HALT: /* Halt the operating system. */

break;

case SYS_EXIT: /* Terminate this process. */

break;

case SYS_EXEC: /* Start another process. */

break;

case SYS_WAIT: /* Wait for a child process to die. */

break;

case SYS_CREATE: /* Create a file. */

break;

case SYS_REMOVE: /* Delete a file. */

break;

case SYS_OPEN: /* Open a file. */

break;

case SYS_FILESIZE: /* Obtain a file's size. */

break;

case SYS_READ: /* Read from a file. */

break;

case SYS_WRITE: /* Write to a file. */

break;

case SYS_SEEK: /* Change position in a file. */

break;

case SYS_TELL: /* Report current position in a file. */

break;

case SYS_CLOSE: /* Close a file. */

break;

}

printf("system call! %d\n", *(int32_t*)(f->esp));

thread_exit();

}

You can examine which system call is invoked for echo x by printing f->esp in the system call handler. The echo command corresponds to system call number 9, particular to the write system call. Thus, we need to implement the appropriate system call based on the provided syscall number.

3.1 Address Validity Check

Prior to implementing and invoking system calls, we must check whether the addresses passed to the system call handler are valid. What constitutes an invalid address? The project presentation provided by the school explains this clearly.

Hence, let’s implement the check_address function that will determine whether a specific address is valid. The required functions are pagedir_get_page from userprog/pagedir.c and is_user_vaddr from threads/vaddr.h. The pagedir_get_page also requires a pagedir as an argument, which is the current thread’s pagedir.

The implemented check_address function looks like this:

void check_address(void* vaddr) {

if (vaddr == NULL) { exit(-1); }

if (!is_user_vaddr(vaddr)) { exit(-1); }

if (pagedir_get_page(thread_current()->pagedir, vaddr) == NULL) { exit(-1); }

}

This function will be used to verify the addresses of arguments received by the system call function, such as esp + 4, esp + 8, and so forth.

3.2 Implementing System Calls

Let’s implement each system call function. We will reference the Pintos Official Manual and the project PPT provided by the school. First, declare the prototypes for the system calls in userprog/syscall.h. As some functions return a boolean type, include stdbool.h as well.

// src/userprog/syscall.h

#ifndef USERPROG_SYSCALL_H

#define USERPROG_SYSCALL_H

#include <stdbool.h>

typedef int pid_t;

void syscall_init(void);

void check_address(void* vaddr);

void halt(void);

void exit(int status);

pid_t exec(const char *cmd_line);

int wait(pid_t pid);

bool create(const char* file, unsigned int initial_size);

bool remove(const char* file);

int open(const char* file);

int filesize(int fd);

int read(int fd, void *buffer, unsigned int size);

int write(int fd, const void* buffer, unsigned int size);

void seek(int fd, unsigned int position);

unsigned int tell(int fd);

void close(int fd);

int fibonacci(int n);

int max_of_four_int(int a, int b, int c, int d);

#endif /* userprog/syscall.h */

For Project 1, we need to implement halt, exit, exec, and wait, while ensuring that read functions for stdin and write functions for stdout behave correctly. Additionally, we will need to implement the extra system calls fibonacci and max_of_four_int, but this will be addressed in future projects. We will implement the required functions in syscall.c.

3.2.1 Halt

The halt function calls shutdown_power_off() from src/devices/shutdown.c, which is responsible for shutting down Pintos.

// src/userprog/syscall.c

void halt(void) {

shutdown_power_off();

}

3.2.2 Exit

The exit function terminates the currently running process. It receives the exit status as an argument, which is the value returned to the parent process by calling wait().

This exit function should store the exit status in thread_current()->exit_status, allowing parents to retrieve it. Thus, we need to implement the exit function and ensure that the exit status is saved correctly when invoking thread_exit(). However, a problem arises; the thread structure does not currently have an element to represent the process's exit status.

Therefore, we will add the exit_status member to the thread structure in src/threads/thread.h:

// src/threads/thread.h thread structure snippet

#ifdef USERPROG

/* Owned by userprog/process.c. */

uint32_t *pagedir; /* Page directory. */

int exit_status;

#endif

Now we can implement the exit function. We refer to the implementation guidance provided on page 80 of the Hanyang University PPT.

// src/userprog/syscall.c

void exit(int status) {

struct thread *t = thread_current();

printf("%s: exit(%d)\n", thread_name(), status);

t->exit_status = status;

thread_exit();

}

3.2.3 Exec

The exec function will simply call process_execute.

// src/userprog/syscall.c

pid_t exec(const char *cmd_line) {

process_execute(cmd_line);

}

3.2.4 Wait

The wait function will call process_wait. Once again, remember that process_wait is simply a two-second wait at the moment. We will implement more later.

// src/userprog/syscall.c

int wait(pid_t pid) {

process_wait(pid);

}

3.2.5 Read

The read function will utilize input_getc() from src/devices/input.c, which returns characters from keyboard input. For now, since we only support stdin, if the provided fd is not 0, it returns -1.

// src/userprog/syscall.c

int read(int fd, void *buffer, unsigned int size) {

// not from STDIN

unsigned int cnt;

uint8_t temp;

if (fd == 0) {

cnt = 0;

for (cnt = 0; (cnt < size) && (temp = input_getc()); cnt++) {

*(uint8_t*)(buffer + cnt) = temp;

}

return cnt;

} else {

return -1;

}

}

3.2.6 Write

The write function will use the putbuf function found in <stdio.h>. Similarly, since we will only implement stdout for now, it will return -1 if fd is not equal to 1.

int write(int fd, const void* buffer, unsigned int size) {

if (fd == 1) {

putbuf(buffer, size);

return size;

}

return -1;

}

3.3 Testing

Add the functions implemented so far into the system call handler and run the echo x command once more. Within syscall_handler, we should add the execution of the system call functions and ensure that the addresses of the function arguments are checked for validity beforehand.

// src/userprog/syscall.c

static void

syscall_handler (struct intr_frame *f UNUSED) {

switch (*(int32_t*)(f->esp)) {

case SYS_HALT: /* Halt the operating system. */

halt();

break;

case SYS_EXIT: /* Terminate this process. */

check_address(f->esp + 4);

exit(*(int*)(f->esp + 4));

break;

case SYS_EXEC: /* Start another process. */

check_address(f->esp + 4);

f->eax = exec((char*)*(uint32_t*)(f->esp + 4));

break;

case SYS_WAIT: /* Wait for a child process to die. */

check_address(f->esp + 4);

f->eax = wait(*(uint32_t*)(f->esp + 4));

break;

case SYS_CREATE: /* Create a file. */

break;

case SYS_REMOVE: /* Delete a file. */

break;

case SYS_OPEN: /* Open a file. */

break;

case SYS_FILESIZE: /* Obtain a file's size. */

break;

case SYS_READ: /* Read from a file. */

check_address(f->esp + 4);

check_address(f->esp + 8);

check_address(f->esp + 12);

f->eax = read((int)*(uint32_t*)(f->esp + 4), (void*)*(uint32_t*)(f->esp + 8),

(unsigned)*(uint32_t*)(f->esp + 12));

break;

case SYS_WRITE: /* Write to a file. */

//printf("write system call!\n");

check_address(f->esp + 4);

check_address(f->esp + 8);

check_address(f->esp + 12);

f->eax = write((int)*(uint32_t*)(f->esp + 4), (const void*)*(uint32_t*)(f->esp + 8),

(unsigned)*(uint32_t*)(f->esp + 12));

break;

case SYS_SEEK: /* Change position in a file. */

break;

case SYS_TELL: /* Report current position in a file. */

break;

case SYS_CLOSE: /* Close a file. */

break;

}

//printf("system call! %d\n", *(int32_t*)(f->esp));

thread_exit();

}

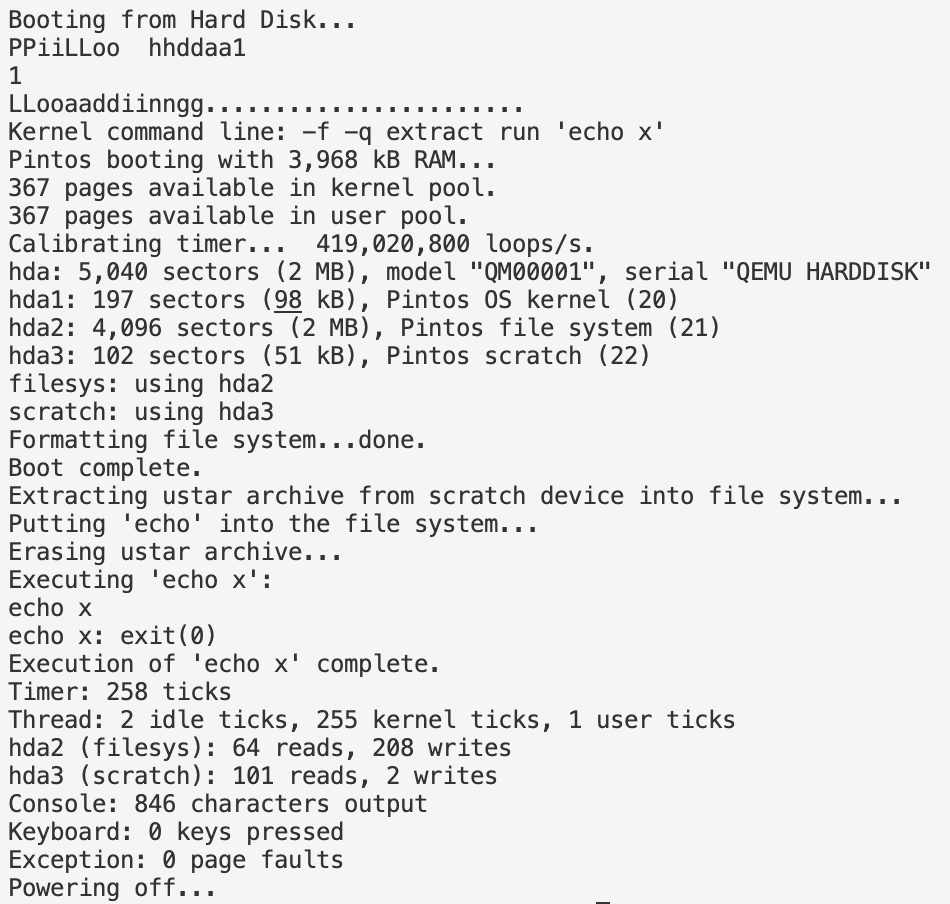

Now run make and execute the echo x command. If it's not working correctly, it's likely that the last line of the syscall handler where it calls thread_exit() is preventing the handler function from proceeding further. Comment out that line.

After making these changes, executing echo x should function appropriately.

Now trying make check will initially show failing tests. Let's address the failure particularly with args-single by reviewing its associated files to see why it failed. The reason is linked to how we parse the file name.

For example, when given the command args-many a b c, it should execute the corresponding file for args-many, but it is instead interpreting args-many a b c as the file name.

This issue can be easily rectified by modifying the process_execute function in userprog/process.c, changing how file names are passed when calling thread_create. We'll only pass the first word of the file name.

Modify the process_execute function as follows:

tid_t

process_execute (const char *file_name) {

char *fn_copy;

tid_t tid;

char file_name_copy[1000];

char* parsed_file_name;

char* save_ptr;

/* Make a copy of FILE_NAME.

Otherwise there's a race between the caller and load(). */

fn_copy = palloc_get_page(0);

if (fn_copy == NULL)

return TID_ERROR;

strlcpy(fn_copy, file_name, PGSIZE);

// Parse only the first word

strlcpy(file_name_copy, file_name, strlen(file_name) + 1);

parsed_file_name = strtok_r(file_name_copy, " ", &save_ptr);

/* Create a new thread to execute FILE_NAME. */

tid = thread_create(file_name, PRI_DEFAULT, start_process, fn_copy);

if (tid == TID_ERROR)

palloc_free_page(fn_copy);

return tid;

}

After this, running make check should reveal an increase in passing tests. The args-multiple test may still fail, and this requires debugging for page faults.

3.4 Debugging Page Faults

The first failure occurs in args-multiple due to page faults. These page faults can be resolved by modifying the page_fault function in src/userprog/exception.c to ensure that kernel mode only reads kernel addresses and user mode only reads user addresses.

static void

page_fault (struct intr_frame *f) {

bool not_present; /* True: not-present page, false: writing r/o page. */

bool write; /* True: access was write, false: access was read. */

bool user; /* True: access by user, false: access by kernel. */

void *fault_addr; /* Fault address. */

/* Obtain faulting address, the virtual address that was

accessed to cause the fault. It may point to code or to

data. It is not necessarily the address of the instruction

that caused the fault (that's f->eip).

See [IA32-v2a] "MOV--Move to/from Control Registers" and

[IA32-v3a] 5.15 "Interrupt 14--Page Fault Exception

(#PF)". */

asm ("movl %%cr2, %0" : "=r" (fault_addr));

/* Turn interrupts back on (they were only off so that we could

be assured of reading CR2 before it changed). */

intr_enable();

/* Count page faults. */

page_fault_cnt++;

/* Determine cause. */

not_present = (f->error_code & PF_P) == 0;

write = (f->error_code & PF_W) != 0;

user = (f->error_code & PF_U) != 0;

/* new! Ensure kernel mode reads kernel addresses only and

user mode reads user addresses only. If not, exit system call.

Additionally handle not_present cases */

if (not_present) { exit(-1); }

if (!user && !is_kernel_vaddr(fault_addr)) {

exit(-1);

}

if (user && !is_user_vaddr(fault_addr)) {

exit(-1);

}

/* To implement virtual memory, delete the rest of the function

body, and replace it with code that brings in the page to

which fault_addr refers. */

printf("Page fault at %p: %s error %s page in %s context.\n",

fault_addr,

not_present ? "not present" : "rights violation",

write ? "writing" : "reading",

user ? "user" : "kernel");

kill(f);

}

Once this is done, page faults should no longer occur during args-multiple. However, if the arguments are not displayed correctly, we may have an issue in the stack structure implementation. Despite thorough checks, I don't currently see a specific problem. It seems as though we might be encountering problems from implementations not yet completed, so we will proceed to the next point of our project structure.

4. Implementing Wait

4.1 Project Structure Implementation

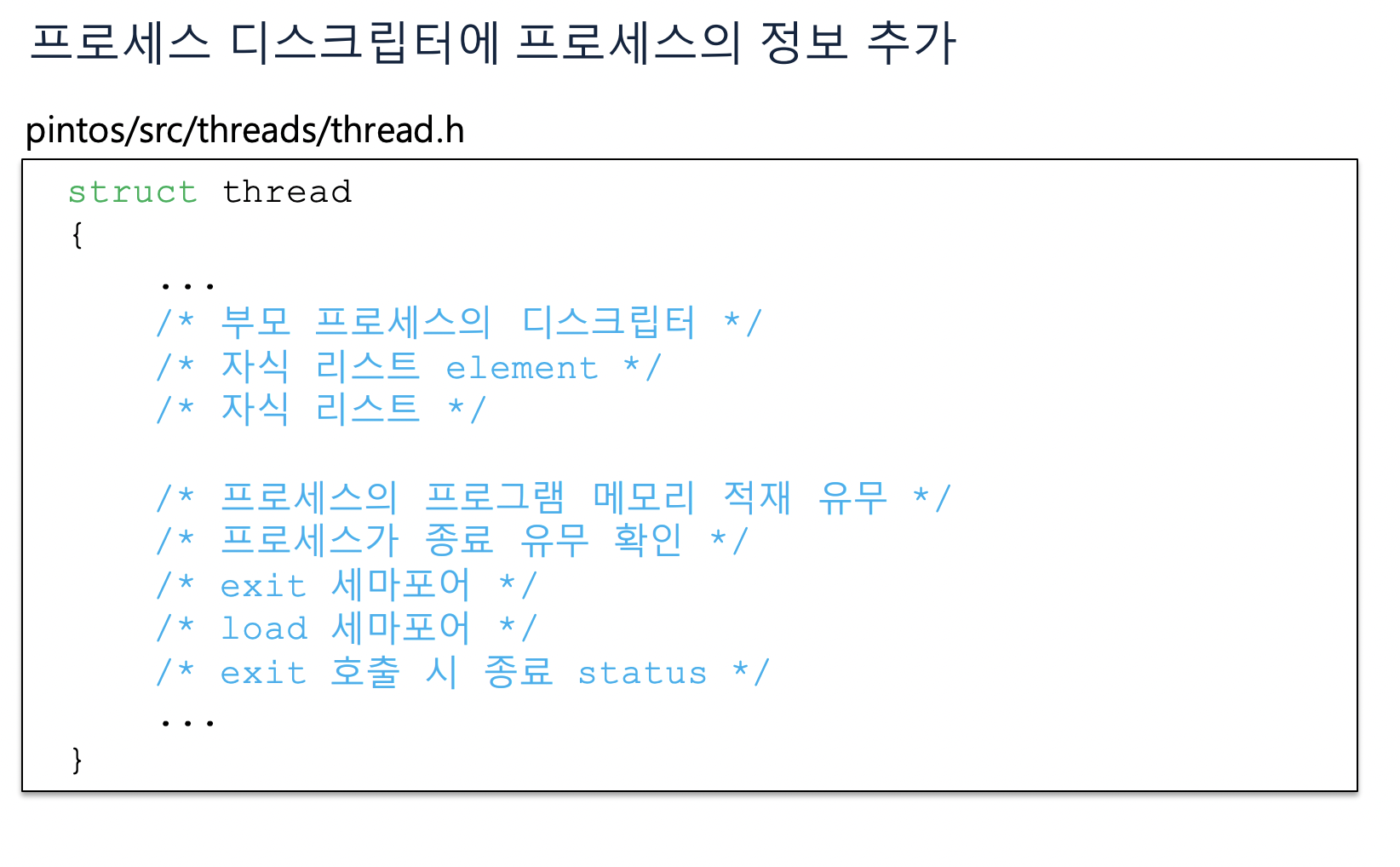

The wait function allows the parent process to wait until the child process has terminated. However, the current thread structure lacks information on differentiating parent from child processes. Therefore, we will add this information to the thread structure and also implement the necessary functions for convenient hierarchical use.

Referencing the PPT from Hanyang University, we will add the following information to the thread structure.

Thus, we will include the following in the thread structure near where we added exit_status earlier.

#ifdef USERPROG

/* Owned by userprog/process.c. */

uint32_t *pagedir; /* Page directory. */

// Parent process descriptor

struct thread* parent_thread;

/* Each structure that is a potential list element must embed

a struct list_elem member. */

/* Child list element */

struct list_elem child_thread_elem;

/* Child list */

struct list child_threads;

/* Flag to indicate loading of the process's program memory */

bool load_flag;

/* Flag to check process exit status */

bool exit_flag;

/* Exit semaphore; semaphore for waiting on child termination */

struct semaphore exit_sema;

/* Load semaphore; semaphore for waiting on child creation */

struct semaphore load_sema;

/* Exit status on exit call */

int exit_status;

#endif

Now, in src/threads/thread.c, in the init_thread function, we will include the initialization for these new elements in the thread structure.

#ifdef USERPROG

/* Initialize child list */

list_init(&(t->child_threads));

// Push to the child list of the running thread

list_push_back(&(running_thread()->child_threads), &(t->child_thread_elem));

// Save parent process

t->parent_thread = running_thread();

sema_init(&(t->exit_sema), 0);

sema_init(&(t->load_sema), 0);

#endif

Now we also need to create a function that searches and returns a thread with a specific pid from the child process.

struct thread* get_child_process(pid_t pid) {

struct thread* child_thread;

struct list_elem* elem;

for (elem = list_begin(&(thread_current()->child_threads)); elem != list_end(&(thread_current()->child_threads)); elem = list_next(elem)) {

child_thread = list_entry(elem, struct thread, child_thread_elem);

if (pid == child_thread->tid) {

return child_thread;

}

}

// Return NULL if not found in the list

return NULL;

}

4.2 Implementing process_wait

In the process_wait function, what must we do? We need to wait for the thread with the corresponding tid to terminate. We will use a semaphore to implement this, where the child process uses sema_down while waiting, and the child process uses sema_up upon termination.

// src/userprog/process.c

int process_wait(tid_t child_tid UNUSED) {

struct thread* child_thread;

struct list_elem* elem;

int exit_status;

child_thread = get_child_process(child_tid);

// Child thread not found

if (child_thread == NULL) {

return -1;

}

// Wait until child process terminates

sema_down(&(child_thread->exit_sema));

exit_status = child_thread->exit_status;

list_remove(&(child_thread->child_thread_elem));

return exit_status;

}

Moreover, the thread_exit function will also need to release the semaphore for the parent process after the child has terminated.

// src/threads/thread.c

void thread_exit(void) {

ASSERT(!intr_context());

#ifdef USERPROG

process_exit();

#endif

/* Remove thread from all threads list, set our status to dying,

and schedule another process. That process will destroy us

when it calls thread_schedule_tail(). */

intr_disable();

list_remove(&thread_current()->allelem);

// Release the waiting state of the parent process.

sema_up(&(thread_current()->exit_sema));

thread_current()->status = THREAD_DYING;

schedule();

NOT_REACHED();

}

However, a problem arises here. The parent process waits for the termination of its child process. When the child process terminates, it invokes sema_up, causing the parent process to resume. The parent then lists the child process and saves the exit status. But the issue is that the child process may no longer be in existence. That's the crux of the problem; one process terminates while the other one requires its details.

The child's memory descriptor should not be released immediately after a termination. Thus, the deletion of the memory in src/userprog/thread.c from thread_schedule_tail should be modified.

void thread_schedule_tail(struct thread *prev) {

struct thread *cur = running_thread();

ASSERT(intr_get_level() == INTR_OFF);

/* Mark us as running. */

cur->status = THREAD_RUNNING;

/* Start new time slice. */

thread_ticks = 0;

#ifdef USERPROG

/* Activate the new address space. */

process_activate();

#endif

/* If the thread we switched from is dying, destroy its struct

thread. This must happen late so that thread_exit() doesn't

pull out the rug under itself. (We don't free

initial_thread because its memory was not obtained via

palloc().) */

if (prev != NULL && prev->status == THREAD_DYING && prev != initial_thread) {

ASSERT(prev != cur);

/* Comment out this line to prevent the deletion of the process descriptor */

// palloc_free_page(prev);

}

}

With these changes, many issues should resolve. Now executing make check should yield at least 46 passing tests of the total 80, with all 21 tests required for Project 1 passing.

pass tests/userprog/args-none

pass tests/userprog/args-single

pass tests/userprog/args-multiple

pass tests/userprog/args-many

pass tests/userprog/args-dbl-space

pass tests/userprog/sc-bad-sp

pass tests/userprog/sc-bad-arg

pass tests/userprog/sc-boundary

pass tests/userprog/sc-boundary-2

pass tests/userprog/sc-boundary-3

pass tests/userprog/halt

pass tests/userprog/exit

pass tests/userprog/create-normal

FAIL tests/userprog/create-empty

FAIL tests/userprog/create-null

FAIL tests/userprog/create-bad-ptr

FAIL tests/userprog/create-long

FAIL tests/userprog/create-exists

pass tests/userprog/create-bound

pass tests/userprog/open-normal

FAIL tests/userprog/open-missing

pass tests/userprog/open-boundary

FAIL tests/userprog/open-empty

pass tests/userprog/open-null

FAIL tests/userprog/open-bad-ptr

pass tests/userprog/open-twice

pass tests/userprog/close-normal

FAIL tests/userprog/close-twice

pass tests/userprog/close-stdin

pass tests/userprog/close-stdout

pass tests/userprog/close-bad-fd

FAIL tests/userprog/read-normal

FAIL tests/userprog/read-bad-ptr

FAIL tests/userprog/read-boundary

FAIL tests/userprog/read-zero

pass tests/userprog/read-stdout

pass tests/userprog/read-bad-fd

FAIL tests/userprog/write-normal

FAIL tests/userprog/write-bad-ptr

FAIL tests/userprog/write-boundary

FAIL tests/userprog/write-zero

pass tests/userprog/write-stdin

pass tests/userprog/write-bad-fd

pass tests/userprog/exec-once

pass tests/userprog/exec-arg

pass tests/userprog/exec-bound

pass tests/userprog/exec-bound-2

pass tests/userprog/exec-bound-3

pass tests/userprog/exec-multiple

pass tests/userprog/exec-missing

pass tests/userprog/exec-bad-ptr

pass tests/userprog/wait-simple

pass tests/userprog/wait-twice

pass tests/userprog/wait-killed

pass tests/userprog/wait-bad-pid

pass tests/userprog/multi-recurse

FAIL tests/userprog/multi-child-fd

FAIL tests/userprog/rox-simple

FAIL tests/userprog/rox-child

FAIL tests/userprog/rox-multichild

pass tests/userprog/bad-read

pass tests/userprog/bad-write

pass tests/userprog/bad-read2

pass tests/userprog/bad-write2

pass tests/userprog/bad-jump

pass tests/userprog/bad-jump2

FAIL tests/userprog/no-vm/multi-oom

FAIL tests/filesys/base/lg-create

FAIL tests/filesys/base/lg-full

FAIL tests/filesys/base/lg-random

FAIL tests/filesys/base/lg-seq-block

FAIL tests/filesys/base/lg-seq-random

FAIL tests/filesys/base/sm-create

FAIL tests/filesys/base/sm-full

FAIL tests/filesys/base/sm-random

FAIL tests/filesys/base/sm-seq-block

FAIL tests/filesys/base/sm-seq-random

FAIL tests/filesys/base/syn-read

FAIL tests/filesys/base/syn-remove

FAIL tests/filesys/base/syn-write

34 of 80 tests failed.

References

Pintos Official Manual https://web.stanford.edu/class/cs140/projects/pintos/pintos.pdf

Hanyang University Pintos PPT https://oslab.kaist.ac.kr/wp-content/uploads/esos_files/courseware/undergraduate/PINTOS/Pintos_all.pdf

A Senior’s Blog on Naver https://m.blog.naver.com/adobeillustrator/220843740425