Exploring TypeScript - Variance and TS

This article is currently in progress.

- This article assumes that the reader is familiar with basic type system concepts such as supertype, subtype, and generics.

In order to better understand TS, I encountered the concept of variance while studying type systems. Consequently, I wrote two articles on this subject. In the first article, I explored what variance is. In this second article (this article), we will examine several aspects of how the concept of variance is integrated into TS.

This article will provide an overview of how TS handles variance and interesting facts about its approach.

The language used in this article follows TS syntax unless stated otherwise.

Additionally, the term immutable, which is commonly translated as "불변," will be kept as "immutable" to avoid confusion with invariance. The opposite concept, mutable, will also be retained as "mutable."

Translations of other terms related to variance, such as covariance, contravariance, invariance, and bivariance, follow Hong Jae-min's translation in Robust Polymorphism with Types.

1. Handling Variance in TS

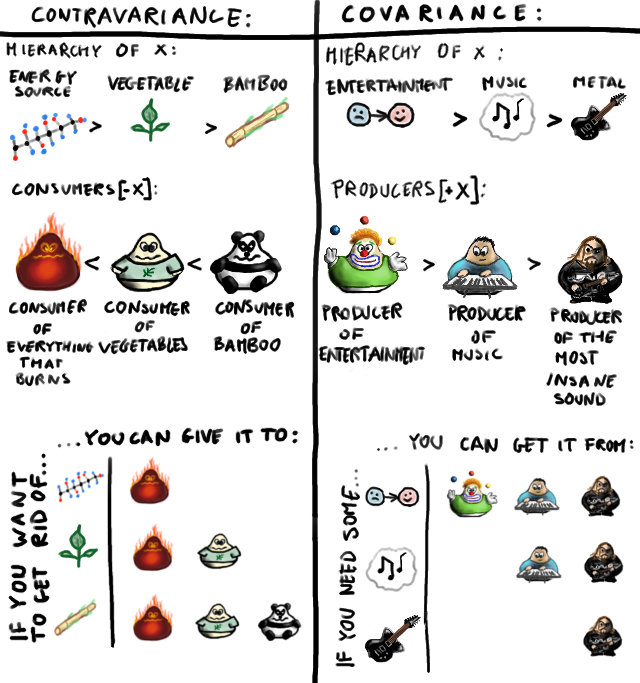

In Exploring TypeScript - What is Variance?, we examined the different types of variance and the ways to establish them. How does TS manage variance?

1.1. Basic Variance Settings

The way TS's type system handles variance is fundamentally as follows:

- By default, it is covariant.

- If the

strictFunctionTypesoption in tsconfig.json is true, function parameters are contravariant; if false, they are bivariant.

Therefore, types like Array<T> are covariant. For example, since number is a subtype of string | number, Array<number> is a subtype of Array<string | number>.

const numberArray: Array<number> = [1, 2, 3];

// stringNumberArray references the same array object as numberArray

const stringNumberArray: Array<string | number> = numberArray;

Also, since TS determines subtyping through structure, the type checker automatically infers the subtype relationships and applies the basic variance settings above.

In the following example, there is no specified subtype relationship between Person and Student. Yet, the type checker infers that Student is a subtype of Person, and it views ReadOnlyList<T> as covariant.

interface Person {

age: number;

}

interface Student {

age: number;

grade: number;

}

class ReadOnlyList<T> {

arr: Array<T>;

get: (idx: number) => T = (idx: number) => { return this.arr[idx]; };

constructor(arr: Array<T>) {

this.arr = arr;

}

}

let list: ReadOnlyList<Person> = new ReadOnlyList<Student>([]);

// list2 assignment results in an error - cannot assign ReadOnlyList<Person> to ReadOnlyList<Student>

let list2: ReadOnlyList<Student> = new ReadOnlyList<Person>([]);

A similar pattern can be observed for the contravariance of function parameter types, where subtype relationships are automatically inferred and function correctly.

Of course, if you define subtype relationships with the extends keyword, it also works properly.

1.2. Setting Variance Manually

So can we use the previously mentioned keywords in and out to manually set variance in TS?

TS introduced Variance Annotations for generic type parameters in TypeScript 4.7, allowing variance to be set using the in and out keywords, which must be specified at the time of definition, not when using generics.

As discussed in Exploring TypeScript - What is Variance?, using in sets contravariance and using out sets covariance. Using both, as in in out, makes the generic type parameter invariant.

// T is covariant

interface ReadOnlyList<out T> {

// T is used only as the method return type

get: (idx: number) => T = (idx: number) => { return this.arr[idx]; };

// ...

}

// T is contravariant

interface Store<in T> {

// T is used only as the method parameter type

set: (idx: number, value: T) => void = (idx: number, value: T) => { this.arr[idx] = value; };

// ...

}

According to this PR, the Variance Annotation clarifies the use of parameters and increases the speed of type checking. The updated documentation states:

It can be understood that whenever thinking about variance is needed, you should use

outfor output andinfor input.

Originally, TS did not have these keywords, but as mentioned, they were introduced in 4.7 to improve code readability, compiler speed, and accuracy. However, it is still recommended to consider carefully the usage of these keywords in the TS community.

More about this can be found in Dogdriip's article on TS Variance Annotation.

2. How TS's Generics Came to Be

Why does TS treat generics, excluding function parameters, as covariant by default?

2.1. Generics in Other Languages

In languages like C#, Kotlin, and Scala, generics are primarily invariant. For generics that require variance, the in and out keywords are used for explicit variance specification.

For example, in Kotlin, you can specify variance for generic type parameters using the keywords in and out. Using in indicates contravariance, out indicates covariance, and not using any keywords suggests invariance.

// Animal is invariant

fun foo(arg: Generic<Animal>) {

arg.walk()

}

// Animal is covariant

fun foo(arg: Generic<out Animal>) {

arg.walk()

}

// Animal is contravariant

fun foo(arg: Generic<in Animal>) {

arg.walk()

}

Generic types defined in the language, such as List<T> and Comparator<T>, specify their variance separately.

2.2. Reasons for Lack of Explicit Variance Specification in TS

In fact, the proposal to introduce variance specification in TS has existed for a long time. The suggestion to incorporate in and out keywords related to variance was raised as early as December 2014.

Subsequently, there were enhanced proposals to resolve issues such as the covariance of Array<T> which included bivariant specifiers, and suggestions to make generics invariant by default and allow variance specification at the point of use of the generic type.

However, for various reasons, the TS team did not accept these proposals for a long time. It wasn't until 2022 that they introduced optional variance annotations for generic type parameters.

So why did TS initially reject such variance specification methods? It could have followed a similar path as other languages by making generics invariant by default and enabling direct variance specification for naturally covariant generics like Array<T> using in and out.

2.3. TS's Decision

In the absence of a method to specify variance, TS faced a choice regarding how to handle common generic types like Array<T>: Should they be made invariant or should the default variance for generic types be set to covariant at the expense of potentially introducing holes in the type system while maintaining intuitive generic subtype relationships?

There are PR comments that reflect these deliberations, such as in TS Issue #6102 comment. If all generic types were made invariant, structural type checking would need to be performed on all derived types, significantly impacting compiler performance. Moreover, it would lead to non-intuitive behaviors where Array<Derived> could not be assigned to Array<Base>.

Interestingly, phrases like "We chatted about this for a while in the team room." or mentions of discussions involving any team members regarding issues are often found in TS issues. It indicates that many decisions are made in meetings besides commenting on GitHub.

Ultimately, the TS community opted to prioritize intuitive subtype relationships by treating generics as covariant by default, even at the cost of introducing some inconsistencies into the type system. As we will see later, the TS team took measures to ensure that this basic variance setting operated as logically as possible. Given the lack of mechanisms to deviate generics from invariance at that time, this choice was reasonable.

As a result, generics, including Array<T> (excluding function parameters), operate as covariant by default.

Furthermore, considering that the TS goal is not to create a fully sound type system and acknowledging JS's operational dynamics, this choice can also be regarded as rational from the perspective of modeling JS through types.

In the following sections, we will explore other aspects of how TS handles variance.

3. Bivariant Function Parameter Types in TS

It was stated that TS is primarily covariant, with function parameters being contravariant. However, when the strictFunctionTypes option is false, function parameters become bivariant.

Bivariance means that a generic type uses the subtype relationship of its type arguments in both directions. If

Tis a subtype ofU, thenArray<T>is a subtype ofArray<U>while also being a supertype.

Moreover, even when the strictFunctionTypes option is true, function parameters can act as bivariant in certain cases, particularly in the case of shorthand method declarations.

// When strictFunctionTypes is true

// T is contravariant

interface Store<T> {

set: (item: T) => void;

}

// T is bivariant

interface Store<T> {

set(item: T): void;

}

What is the rationale behind this? There is indeed a reason, and it is utilized in specific scenarios.

3.1. The Reason

This stems from the same reasoning as before. Since there was no way to explicitly specify variance in TS, it is necessary to ensure that types operate intuitively in such cases.

Let’s assume Dog is a subtype of Animal. Then, is Array<Dog> a subtype of Array<Animal>? It seems reasonable to say that an array of dog objects can also be an array of animal objects.

Following the subtype relationship, all members of Array<Dog> should be assignable to Array<Animal>. If this were the case, then the type (item: Dog) => number should be assignable to (item: Animal) => number.

This is because Array.prototype.push has the type (item: T) => number. (In fact, Array.prototype.push returns the size of the newly created array, hence the return type is a number.)

However, as we have seen, if function parameter types are contravariant, then saying that (item: Dog) => number is assignable to (item: Animal) => number would imply that Animal is assignable to Dog. This creates a contradiction where Array<Dog> cannot be assigned to Array<Animal}.

Thus, in the case where function parameter types are enforced as contravariant, to maintain that Array<subtype> is a subtype of Array<supertype}, (item: subtype) => void must be a subtype of (item: supertype) => void.

This is equal to saying that supertype must be a subtype of subtype, leading to the conclusion that Array<supertype> would then have to be a subtype of Array<subtype}, which is generally not permissible.

Therefore, to handle this special case concerning function parameter types, they were adjusted to behave bivariantly at the expense of some precision.

In languages like C#, where keywords such as in and out can specify variance, these issues can be resolved. However, since TS did not have such keywords initially and, even now, tends to avoid heavy reliance on the concept because it is complex, the bivariant treatment for these parameters emerged.

From the perspective of TS designers, it is necessary to account for these aspects in the design. However, for users, having function parameter types behave bivariantly does not offer much benefit. Therefore, when the --strictFunctionTypes flag is set to true, function parameter types are enforced as contravariant.

Notably, even in such scenarios, method parameter types declared in shorthand notation operate bivariantly. Methods like push are defined in this manner. This ensures that the intuitive behavior of covariant types like Array<T> remains consistent.

interface Array<T> {

// ...

push(...items: T[]): number;

// ...

}

3.2. Bivariance Hack

Interestingly, there exists a mechanism to enable function parameter types to behave bivariantly even when the strictFunctionTypes option is true.

This is known as the bivarianceHack, which is commonly observed in React's useRef callbacks and event handler types.

// @types/react/index.d.ts

// Bivariance hack for consistent unsoundness with RefObject

type RefCallback<T> = { bivarianceHack(instance: T | null): void }["bivarianceHack"];

type EventHandler<E extends SyntheticEvent<any>> = { bivarianceHack(event: E): void }["bivarianceHack"];

Instances of this can also be found in type definition files for libraries like Backbone.

3.3. UnionToIntersection

3.4. Types of All Functions

Consider the following code where a function with a parameter of type never is assigned a function with a parameter of type number, which does not lead to an error.

type funcType = (a: never) => number;

const foo: funcType = (a: number) => a + 1;

This behavior contradicts what we would generally expect in TypeScript. For instance, if we try to assign a number array to a never array, it results in an error.

type neverArray = never[];

// Error

// Type 'number' is not assignable to type 'never'.

const arr: neverArray = [1, 2, 3];

4. Handling Immutable Types in TS

In the previous section, we examined the fact that function parameter types are bivariant and the reasons for this behavior. Ultimately, the reality that TypeScript does not allow explicit variance specification for generic type parameters led to these compromises. But why were such compromises necessary in the first place? Is there any fundamental way to resolve this problem?

4.1. Conception

While there may be additional minor reasons, the fundamental reason for needing to create bivariant parameter types stems from the existence of mutable objects, like arrays, in JS. In JS, it is incredibly easy to change the referenced objects!

Issues arising from such mutable objects also appear in other languages that allow explicit variance specifications for generic type parameters. For instance, in Kotlin, both MutableList<T> and List<T> exist, where MutableList<T> is invariant and List<T> is covariant. In fact, mutable objects cause even greater problems, such as side effects and issues in multithreaded environments.

Could we solve these problems entirely? By always treating variables as immutable and either ignoring mutable objects or handling them differently. This paradigm is indeed utilized in various contexts. On a smaller scale, consider how React addresses immutability, and, on a larger scale, consider the functional programming paradigm, which advocates for treating all objects as immutable and structuring programs with pure functions.

The advantages of managing objects immutably in React or the benefits of functional programming pertain to topics beyond the scope of this article. However, discussing immutability does generate intriguing discussions related to generic variance, prompting us to delve into this area.

4.2. Concat

In JS, there are several methods for dealing with arrays immutably. Common examples include concat, filter, and map. These array methods return a new array instead of modifying the original. How are their types defined? Starting with the most interesting, let's take a look at concat, which is defined with two overloads.

interface Array<T> {

concat(...items: ConcatArray<T>[]): T[];

concat(...items: (T | ConcatArray<T>)[]): T[];

}

Additionally, ConcatArray<T> is defined as follows.

interface ConcatArray<T> {

readonly length: number;

readonly [n: number]: T;

join(separator?: string): string;

slice(start?: number, end?: number): T[];

}

ConcatArray<T> contains the necessary properties for an array and its methods join and slice. It is entirely covariant.

https://witch.work/posts/typescript-concat-type-history

References

Hong Jae-min, "Robust Polymorphism with Types" https://product.kyobobook.co.kr/detail/S000210397750

What are Covariance and Contravariance? https://edykim.com/ko/post/what-are-covariance-and-contravariance/

Variance in TypeScript https://saramkim.github.io/Variance/

Variance in Type Systems – Covariance and Contravariance https://driip.me/d875a384-3fb9-471b-a53b-b3ca52f8238e

Variance Annotations for Type Parameters Added in TypeScript 4.7 https://driip.me/644e7f06-8591-443e-9fca-44b0ab424fda

Variance in TypeScript: Why Was It Developed This Way? https://driip.me/d230be64-df1d-4e9a-a8c2-cba6bbc0ae15

What is Covariance? https://seob.dev/posts/%EA%B3%B5%EB%B3%80%EC%84%B1%EC%9D%B4%EB%9E%80-%EB%AC%B4%EC%97%87%EC%9D%B8%EA%B0%80/

Creating Variant Generic Interfaces (C#) https://learn.microsoft.com/ko-kr/dotnet/csharp/programming-guide/concepts/covariance-contravariance/creating-variant-generic-interfaces

TS 4.7 Release Notes, Optional Variance Annotations for Type Parameters https://devblogs.microsoft.com/typescript/announcing-typescript-4-7/#optional-variance-annotations-for-type-parameters

TS FAQ, "Why are function parameters bivariant?" https://github.com/Microsoft/TypeScript/wiki/FAQ#why-are-function-parameters-bivariant

The Issue of Adding Covariance/Contravariance Annotations – Proposal and Rejection Reasons https://github.com/microsoft/TypeScript/issues/1394

Proposal: Covariance and Contravariance Generic Type Argument Annotations https://github.com/microsoft/TypeScript/issues/10717

Strict Function Types PR https://github.com/microsoft/TypeScript/pull/18654

Allow a flag that turns off covariant parameters when checking function assignability https://github.com/microsoft/TypeScript/issues/6102

What is the purpose of bivarianceHack in TypeScript types? https://stackoverflow.com/questions/52667959/what-is-the-purpose-of-bivariancehack-in-typescript-types

Bivariance hack for consistent unsoundness with RefObject https://www.pumpkiinbell.com/blog/react/ref-callback-bivariance-hack

Variance in programming languages https://rubber-duck-typing.com/posts/2018-05-01-variance-in-programming-languages.html

Why are TypeScript arrays covariant? https://stackoverflow.com/questions/60905518/why-are-typescript-arrays-covariant

A fully-sound type system built on top of existing JS syntax is simply a fool's errand. https://github.com/microsoft/TypeScript/issues/9825#issuecomment-306272034

Docs: function parameter bivariance https://github.com/microsoft/TypeScript/issues/14973

Overloads in Array.concat now handle ReadonlyArray - ConcatArray's introduction in PR https://github.com/microsoft/TypeScript/pull/21462